Click an Image for Full Size

John Quincy Adams

by Unknown Artist, 1885

after Thomas Sully and Gilbert Stuart, 1825–1830, (see p. 70)

JOHN QUINCY ADAMS

Sixth President,

March 4, 1825 – March 4, 1829

![]()

Franklin P. Rice, 1882:

JOHN QUINCY ADAMS, the Sixth President, was born at Braintree, Mass., July 11th, 1767. In 1778, he accompanied his father to France, and in 1780 entered the University at Leyden. He was, soon after, appointed private secretary to Francis Dana, Minister to Russia, and passed a year in St. Petersburg, after which he resumed his studies at the Hague. He returned to the United States and completed his education at Harvard, graduating in 1788. He studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1791. Three years later, President Washington, appointed him Minister to Holland; and he was afterwards transferred to Prussia. He was elected United States Senator from Massachusetts in 1803. Convinced that the leaders of the Federalists, upon the principle that they would rule or ruin, were determined to dissolve the Union and break up the general government, he gave his support to the measures of President Jefferson, was censured by the Legislature, and resigned his seat in the Senate. He was Minister to Russia from 1809 to 1813, and was one of the Commissioners to negotiate the treaty of peace with Great Britain in 1814. He was Minister to England for two years preceding his appointment as Secretary of State by President Monroe. In 1825 Mr. Adams became President, holding the office four years. In 1830 he was elected to Congress, and continued a member of that body the remainder of his life. He died at his post, February 23d, 1848.

Mr. Adams was a thorough scholar, a profound statesman, and an adroit diplomat. Manly, independent, and patriotic, he never in the course of his long public service, swerved from what he believed to be the path of duty. His sturdy battle in defence of the right of petition, and his inflexible resistance to the encroachments of the slave power, entitle him to the veneration of every lover of human freedom. His versatility was wonderful, and his voice was heard upon nearly every important question before the House. His power as a debater gained for him the name of “the Old Man Eloquent.” In the combination of those qualities which form true greatness, his will ever remain a sublime character in American history.

![]()

Henry W. Rugg, 1888:

EARLY IN THE month of February of the year 1778, the good ship Boston lay at anchor in Massachusetts Bay. The frigate was waiting for its distinguished passenger, America’s Ambassador to France, John Adams, who, in company with son, John Quincy, a boy of ten years, went on board the Boston one stormy winter day, leaving his brave wife and little family in the shelter of his native land, while he devoted himself to serving his country’s interests, enduring risks and hardships, sacrificing all personal ambitions at the call of patriotic duty. It was this lad, born in the quiet town of Quincy, Massachusetts, July 11, 1767, separated from his mother and childhood home at so early an age, who afterwards, in the course of events, was called to fill the honored position of Chief Magistrate of this Republic.

Born at too late a period to take part in the Revolutionary War, at a time when the government of the Republic had already been founded, John Quincy Adams early acquired a love of freedom; received as a boy lasting impressions of the meaning of war, the principles of liberty, the resistance of oppression, and the defense of the right. He never forgot the sight he witnessed when only eight years old, the spectacle of burning Charlestown, the smoke from the battle of Bunker Hill, the sounds of war which at that time he heard. On board the Boston, also, there were British frigates encountered, and a prize taken, so that the boy quickly learned the importance attached to his country’s welfare and the services which must be rendered in her behalf. Naturally an intelligent lad, this life of travel and intercourse with distinguished men taught him in ways not possible to the average youth, while to offset this he lost something of the advantages connected with home training and a systematic education.

John Quincy Adams

by John Singleton Copley, 1796

When John Adams again crossed the ocean in 1779, being empowered by the President to negotiate a treaty of peace with Great Britain, John Quincy accompanied his father, traveling with him from Spain to Paris, beginning on this journey to keep a diary, as a record of daily events, a practice which he continued throughout his life. The elder Adams resided for a time in Holland, so the boy was sent to school in Amsterdam, afterwards studying for a brief period in the University of Leyden. When a youth of fifteen, he accompanied Mr. Francis Dana in his unsuccessful mission to St. Petersburg, acting in the capacity of a private secretary. After the journey back to Holland, which he took alone, he joined his father, entering the best society of The Hague and profiting by an intercourse with the diplomats there assembled. When John Adams was appointed Ambassador to the Court of St. James in 1785, his son preferred to return to America, relinquishing the brilliant life in London for the student career of an American college, as he already felt the love for his country and its institutions which afterwards impelled him in his performance of all public service. He graduated from Harvard College with honor, in July, 1787.

The young law student was admitted to the bar in 1791, after having pursued his legal studies under Theophilus Parsons, of Newburyport, afterwards Chief Justice of Massachusetts. He took an interest in public affairs early in life, writing articles upon political subjects, showing very quickly the abilities of a rising young man. In a series of articles published about this time, Mr. Adams argued in favor of the strict neutrality which he thought it was the duty of the United States to maintain in the war impending between France and England. These ideas, in conformity with the thought and policy of President Washington, doubtless influenced him in his choice of Ambassador to The Hague, an appointment which he gave to Adams in the year 1794. Although John Adams was Vice-President at this time, he exercised no influence in securing the appointment of his son, Washington acting in the matter without his counsel or even knowledge. Thus it is that we find John Quincy Adams enjoying the confidence of Washington, honorably identified in carrying out the foreign policy of the United States when only twenty-seven years of age. For two years Mr. Adams remained in Holland. At the expiration of that time, he was appointed Minister to Portugal, but while proceeding to undertake his duties there, he received a new commission, changing his destination to Berlin. His father, at that time President, felt some hesitancy in appointing him fearing public criticism, as personal motives might be thought to influence the action. President Adams asked counsel in this matter of his friend, George Washington, then retired from public office, who replied in a letter bearing testimony to the high esteem in which he held both father and son, one of its clauses being as follows: “I give it as my decided opinion that Mr. Adams is the most valuable public character we have abroad; and that there remains no doubt in my mind, that he will prove himself to be the ablest of all our diplomatic corps.”

Just before proceeding to the Court of Berlin, Mr. Adams, waiting in London for instructions from his government, married Miss Louisa Catherine Johnson, daughter of the American Consul in that city. Mrs. John Quincy Adams would have been a notable woman in any position; as the wife of the distinguished American statesman, she received the respectful homage to which, because of her beauty, accomplishments, and intelligence, she was entitled.

While serving in the capacity of Ambassador to Berlin Mr. Adams conducted negotiations with skillful diplomacy, concluding a commercial treaty with Prussia before he was recalled to this country by President Jefferson in the year 1801. He returned to this

John Quincy Adams

by Gilbert Stuart, 1818

John Quincy Adams

by Thomas Sully and Gilbert Stuart, 1825 - 1830

country with a reputation already established for a scholarly statesmanship, while, on resuming his law practice in Boston, he added to the renown already won by the judicial learning which he displayed. Soon called to public life again, he served one term in the Massachusetts Senate, afterwards, in 1803, he was elected United States Senator. Although in general sympathy with the opinions of the Federal side in politics, Mr. Adams held to more moderate political views; he separated himself almost entirely from his party in supporting the Embargo Bill, which had been recommended by President Jefferson. He was censured for this course by the Massachusetts Legislature, consequently he resigned his place in the Senate, and retired to private life.

During the three years which followed, Mr. Adams not only attended to the duties of his profession, but also ably filled the Chair of Rhetoric and Belles Lettres at Harvard College, giving lectures which were received with approbation by the students and other scholarly men. These lectures were published, attracting favorable notice in the literary as well as the social world. Mr.

John Quincy Adams

by Asher Brown Durand, 1835

Adams returned to public life soon after the accession of Mr. Madison to the presidency, receiving an appointment, in 1809, as United States Minister to Russia. He soon gained the confidence of the Russian Emperor, a valuable influence of good at the time when war broke out between England and the United States, for, as a result of this confidence, Russia offered her mediation to both belligerent nations. Thus it was that, though England declined this offer of mediation, she was led to signify her willingness to deal directly with the United States, and so peace was brought about. Mr. Adams was at the head of the commission which, after six months of negotiation, came to an agreement with the English Commissioners, the treaty of peace being signed at Ghent, December 24, 1814. Shortly after this date Mr. Adams was promoted to fill the office of Minister to England, well performing the duties of this important diplomatic position until he was recalled to his native land in the year 1817 to assume the responsible place of Secretary of State under President Monroe. He acted in this capacity for eight years, helping to shape the foreign policy of Mr. Monroe’s administration, and deserving credit for many of the measures which distinguished that period.

The candidates for the presidency to succeed President Monroe were Andrew Jackson, William Henry Crawford, Henry Clay, and John Quincy Adams. There was no choice made by the electoral college, so the election was by the House of Representatives, voting by states, Mr. Adams being elected as a result of the first ballot.

The administration of President Adams was decidedly unpopular, especially among the friends of General Jackson, whose increased popularity resulted in his election as President over Adams in the campaign of 1828. John Quincy Adams seems to have inherited something of the austerity, coupled with the cold manners, which characterized his father, so that his personality drew towards him few personal or party friends. The younger Adams was not an intense partisan; followed his individual thought to whatever distances it might lead away from his political party, but he was always true to his own best convictions as to his country’s interests and welfare. During his administration there was great material progress throughout the country, the President being foremost to promote all national improvements.

When General Jackson was inaugurated in March of the year 1829, Mr. Adams retired to his home in Quincy, thinking to spend his remaining years on earth quietly as a country gentleman, enjoying the competency afforded him by his father’s fortune in addition to his own. But Massachusetts needed his services; he was elected from his district to Congress, and kept there by repeated re-elections until the time of his death. In Congress he maintained his independent position, holding aloof from both parties to a great extent. He was scholarly, judicial, and able, possessing rare acquisitions for congressional leadership. He struggled persistently for the “right of petition,” and witnessed, in 1845, the abolition of the “gag rule,” restricting the right to petition Congress on the subject of slavery.

It was when the “old man eloquent” was gaining more and more of his associates’ respect and love that he was stricken down, while in the Hall of Representatives, with a paralytic attack, February 21, 1848. He was carried to the Speaker’s room in the Capitol, where, under the roof which had echoed with his ringing speeches in behalf of human rights, he breathed the last feeble words, so consistent with the whole tenor of his life, “This is the end of earth; I am content.”

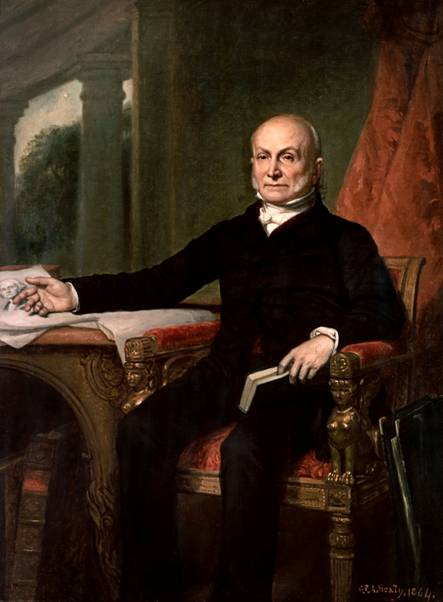

John Quincy Adams

by George Caleb Bingham, c. 1850 (after his 1844 original)

There are two or three notable pictures in the career of this distinguished patriot that come into the mind whenever his name is mentioned. One is of the youthful traveler and associate of celebrated men, early trained into the forms of cultivated society, yet never accommodating himself to the ceremonies foreign to his nature, nor assuming those graceful manners which might have been expected from his education so cosmopolitan in its surroundings.

The second picture is that of the man advanced in life, who, with blazing eyes and a heart beating so warmly in defense of what he thought was the right, stood up in the House of Representatives, making that grand speech which silenced all antagonisms, as he argued in behalf of the petition, objected to by the House, because several of its signatures were those of women.

Again another picture presents itself as the pages of history are reviewed. When, in the reorganization of the Twenty-sixth Congress, December, 1839, the disputed seats of New Jersey occasioned trouble in the choice of speaker, it was John Quincy Adams, who in response to repeated calls, rose, and made a speech advocating decisive action in the matter. When it was asked how the question should be put, as the clerk refused to act, amid tumultuous applause, Mr. Adams replied, “I will put the question myself.” Mr. Wise, of Virginia, in commending this speech said, “If, when you are gathered to your fathers, I were asked to select the words which in my judgment are the best calculated to give at once the character of the man, I would inscribe upon your tomb this sentence, ‘I will put the question myself.’” The world has accepted this epitaph as expressing the force of character possessed by John Quincy Adams, which showed itself, not only in that one memorable act, but in the whole course of his long and useful public career.

![]()

by George P. A. Healy, 1864