Click an Image for Full Size

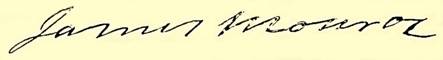

JAMES MONROE

Fifth President,

March 4, 1817 – March 4, 1825

![]()

Franklin P. Rice, 1882:

JAMES MONROE, the Fifth President, was born in Westmoreland County, Virginia, April 28th, 1758. Was educated William and Mary College. He entered the Revolutionary army, participated in several battles, was wounded at Trenton, and attained the rank of captain. After the war he was elected successively to the Virginia Assembly, the General Congress, and in 1790, the United States Senate. He was abroad upon diplomatic missions from 1794 to 1808, excepting three years when he was Governor of Virginia. He was a party to the purchase of Louisiana 1802. After serving again as Governor, Monroe was, in 1811, appointed Secretary of State by President Madison, which office he held for six years. He also acted for a time as Secretary of War, discharging the duties with energy and ability. In 1817, Mr. Monroe became President of the United States, and in 1820 was re-elected by an almost unanimous vote. He died in New York City, July 4th, 1831.

The "Era of Good Feeling" dawned upon Monroe's administration. Party spirit was for the time, totally extinguished. During his term of office the prosperity of the nation rapidly advanced. In 1819, the territory of Florida was acquired from Spain. The Monroe Doctrine — that European interference in the affairs of American States would not be tolerated — was asserted to the world. Much attention was given to internal matters. Surrounded by able advisers his conduct of public affairs was creditable to himself and honorable to the country. He left the reputation of a "discreet and successful statesman, more distinguished for administrative talents than for oratorical powers."

![]()

Henry W. Rugg, 1888:

THE MOST democratic of men must derive a certain amount of pleasure in tracing his ancestry to the distinguished leaders of a past age, to the honest, courageous souls, sometimes of noble name, always of noble nature, who played important parts in shaping the destinies of nations or communities. Certainly it must be admitted that biographers are prone to touch upon the family distinctions of their subject, while readers are always delighted to think of their hero as descended from a notable and historic line of ancestors. Although it is true that great men have sprung from very lowly beginnings, from obscure families of almost unknown origin, it is equally a fact that, even in democratic America, the history of some of her ablest leaders brings them into view as only sharing in the triumphs and distinguished careers of a race born to influence men and affairs. Thus it is that James Monroe, the fifth President of these United States, belonged to an honorable and somewhat influential family, one of his ancestors, Hector Monroe, being prominent among the Scottish cavaliers of the seventeenth century, an officer ardently devoted to the fortunes of that ill-fated monarch, Charles I. The descendants of this Scottish cavalier were prominent among the early settlers of the New World, and the Monroe family, living in Westmoreland County, Virginia, where James was born April 28, 1758, were prosperous and well-known people. It is of interest to note the fact that four of the early Presidents of our Republic, Washington, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe, were born and reared in the same region, lying in the vicinity of the Blue Ridge Mountains; were doubtless affected by the same influences, imbibed the common principles of patriotic zeal, and shared in a like service for their country’s prosperity.

James, the subject of this sketch, was a bright, intelligent boy, a thoughtful student, yet not so devoted to his books as to neglect the sports of boyhood or the enjoyments of out-door life. After an excellent preparation in a classical school, he entered William and Mary College when he was sixteen years of age, having already learned to appreciate the value of the best possible education, as a foundation for life-work in any direction. This was an eventful time in the history of the country. The air was filled with rumors of impending war and it was with difficulty that

Lt. James Monroe is portrayed as the flag bearer just behind Washington in this detail from “Washington Crossing the Delaware” by Emanuel Leutze, 1851

young Monroe could properly attend to his work as a college student. At length his patriotic ardor so impelled him to take active service in defense of his country that he left college in 1776, at once going to General Washington’s headquarters in New York, there taking his place as a volunteer in the ranks of the American army.

Monroe, after following the army in its retreat through New Jersey, taking part in several engagements, was wounded at the battle of Trenton, where he so distinguished himself that he was promoted, receiving a commission as captain. He accepted, a little later, a position on the staff of General Armstrong, doing creditable service in the battles of Brandywine, Germantown, and Monmouth. He was regarded with favor by General Washington, who gave him a commission as colonel, together with the authority to raise and equip a regiment of Virginia volunteers. This undertaking was for many reasons, none of them reflecting upon his ability or patriotism, however, unsuccessful, so that Colonel Monroe decided to carry out his early plan of entering the legal profession, thus ending his military career, although he volunteered, at a later period, in defense of Virginia, and stood always ready to engage in the scenes of battle, whenever his service should be required. He studied law in the office of Mr. Jefferson, then governor of Virginia, who probably did much towards forming the character of the young man, as well as directing his professional studies.

It was but a short time after Monroe began the practice of law that he was called into public life, to take part in the legislative councils of his country. He assumed the responsibilities and duties of a member of the Virginia Legislature in the year 1782, and was a little later chosen by that body as a member of the executive council. He was called to represent Virginia in the Continental Congress of 1783, taking his seat as a member of that body, in time to be a witness of the memorable scene at Annapolis, Maryland, when General Washington resigned his commission to that authority which he always recognized as a supreme power. In the debates of Congress, Colonel Monroe took part with ability and judgment, soon gaining a position of prominence and, young as he was, exerting a very considerable influence. Under a law then in force, he was ineligible for re-election, and retired from the legislature at the expiration of his term of service, in the year 1786. It was during the closing year of his membership in Congress that Monroe met Miss Kortright, whom he married, after a comparatively brief courtship, and with whom he lived happily throughout the half-century of their earthly existence.

While serving in Congress, Mr. Monroe became impressed with the inadequacy of the Articles of Confederation as a form of rule for the government of the new Republic. He deemed these articles unsuitable to the prevailing modes of thought and life among the American people, so he favored the formation of a new constitution which should augment the dignity and power of the central government. When, however, the constitution, framed in 1787, was offered for the public adoption, Monroe opposed its ratification, in the convention of Virginia, where he was a member, because he believed that it would grant too much power to the government, and for other reasons was not what the people required. In following out this course of action, based upon his best judgment, he antagonized the views of Mr. Madison, who had earnestly argued in behalf of the new constitution, and of many others among his associates and friends. The Virginia convention

James Monroe

by Gilbert Stuart, c. 1817

finally adopted the constitution as presented, Mr. Monroe finding himself in the minority. His opinions upon this matter did not seem to affect his popularity among his constituents, for, in 1789, he was elected a United States Senator by the Virginia Legislature. He actively opposed many of the leading features of Washington’s administration, but that great-minded and tolerant President saw only the integrity and honest purpose of Monroe, and retained him in his confidence and friendship, notwithstanding these important differences of opinion. This is shown by Washington’s act in appointing Monroe as Minister to France in 1794, in the place of Governeur Morris, recalled in accordance with the request of the French Government. Monroe, who belonged to the party sympathizing, to a large degree, with the rulers and people of France, was welcomed in that country with great rejoicings and enthusiasm. His course at Paris, however, was not in conformity with President Washington’s ideas as to the strict neutrality which his administration ought to maintain, as between France and England, and in 1796 Mr. Monroe was recalled. In the year 1799, he became governor of Virginia and was twice re-elected to that office. Soon after Jefferson’s accession to the presidency, he was again sent abroad in a diplomatic capacity as Envoy Extraordinary to France, there aiding Mr. Livingston, minister to that country, in his negotiations for the purchase of New Orleans and contiguous territory. Having concluded this special business, he proceeded to England, acting under a commission as minister to that country in place of Rufus King. At this time, also, his services as diplomat were called into requisition to aid in settling a controversy with Spain. This attempt was unsuccessful, as was also the chief purpose he had in view in his relations with England, namely, that of negotiating a treaty with Great Britain, which should be more favorable to the interests of the United States.

Mr. Monroe, who refused to antagonize Madison as a candidate for the presidency, was again elected governor of Virginia, in 1811, but hardly had he entered upon the duties of that office before he was invited to take the place of Secretary of State, that office having been made vacant by the retirement of Robert Smith. Mr. Monroe accepted the appointment and held the office during the remainder of Mr. Madison’s administration. As Secretary of State he took a bold, decided stand against the

James Monroe

by Samuel Morse, c. 1819

encroachments of England, and advocated a policy which resulted in an open rupture with that country in 1812. After the capture of the capital, Mr. Monroe assumed the duties of the war department, in addition to those devolving upon him as Secretary of State, evincing much energy and ability in obtaining supplies and applying measures requisite for a vigorous prosecution of the war. His patriotism was specially shown by pledging his private credit, as subsidiary to that of the government, to provide the needful outfit and equipment for the army defending New Orleans. By this act New Orleans was successfully defended, the British army defeated, and an honorable peace was soon brought about.

Mr. Monroe was elected President in 1816, and re-elected almost unanimously four years later. His administration of the government was marked by a liberal and progressive spirit, and was generally satisfactory. Although a disciple of Jefferson and elected by the Democratic party, he yet chose a course of public action which commended him to the Federalists, while it did not take from him the support of his own party. At that time, however, party lines were well nigh obliterated, old issues had lost their bitterness, and new lines of difference had not yet been marked out. It was indeed an “era of good feeling” when the President found it comparatively easy to bring into his Cabinet prominent men representing both parties, and to pursue a course of administrative action approved by a large majority of the American people. At first he was too strict in his construction of the Constitution, as defining the powers of the general government, to favor a system of internal improvements, but finally he yielded his own scruples in this respect in order to advance the nation’s welfare. His administration was distinguished by the acquisition of Florida, obtained from Spain, in 1819, by the payment of $5,000,000, the admission of five new states, the avowal and insistence of a policy relating to foreign nations, since known as the “Monroe Doctrine,” under which no European interference on this continent was to be allowed, and the passage of the “Missouri Compromise,” after a prolonged struggle over the admission of Missouri, during which the “era of good feeling” was disturbed by the growing hostility manifested between the Slave States and the Free States, and the strife of each section to obtain increase of power. Notwithstanding the feeling thus awakened, the country greatly prospered during

James Monroe

by Gilbert Stuart, c. 1820

the eight years of President Monroe’s administration, marked by many evidences of his wise, patriotic, and statesmanlike career. After leaving the presidential office, he took up his residence at Oak Hill, Loudoun County, Virginia, where he passed the remainder of his years in an honorable retirement. His death occurred July 4, 1831, at the residence of his son-in-law, Samuel L. Goveneur, of New York, with whom he was temporarily residing as guest and visitor.

The men who founded this Republic were influenced in thought, were roused to action, by the self-same principle of patriotic devotion, impelling them to active service in behalf of their native land. With this one motive as a basis for the formation of character each of these early leaders worked out his own personality, exercising his various talents to further the prosperity of his country along individual lines of well-defined, persistent effort. President Monroe was lacking in some of the qualities which distinguished the other patriotic leaders of his time, yet he was a man of intelligent thought, of varied intellectual powers, of dignified bearing, a true patriot and an illustrious statesman. He was thoroughly reliable, an honest gentleman, conducting himself as such in all the high positions of public trust which he was called to fill. He was a true friend to those who enjoyed his confidence, was utterly unselfish, desired his country’s good above all personal considerations, and was a singularly pure-minded product of the best American civilization.

![]()

James Monroe

by Rembrandt Peale, 1817 - 1825