Click an Image for Full Size

ANDREW JACKSON

Seventh President,

March 4, 1829 – March 4, 1837

![]()

Franklin P. Rice, 1882:

ANDREW JACKSON, the Seventh President, was born at Waxhaw, South Carolina, March 15th, 1767. His opportunities for education were few. At the age of fourteen he entered the Revolutionary army and served until the war closed. In 1788 he removed to Nashville, Tennessee, and began the practice of the law. He was United States Senator in 1797, and Judge of the Supreme Court of Tennessee from 1798 to 1804. As Major General of the state militia he took part in the War of 1812, and was given the same rank in the army of the United States. He gained a signal victory over the British at New Orleans in January, 1815. It is upon this event that his fame chiefly rests. He was engaged in the Seminole War in 1817. In 1820 he was Governor of Florida, and again a Senator in 1823. He was elected President of the United States in 1828, and held the office eight years. He died at the Hermitage, near Nashville, Tennessee, June 8th, 1845.

General Jackson possessed but few qualifications for the high office to which he was elevated. He had no learning and but meagre information. Of statesmanship he had no conception. His disposition was arbitrary and his temper ungovernable. But he possessed executive ability, and in an emergency never hesitated to “take the responsibility.” His integrity and patriotism are unquestioned. His administration was stormy, inconsistent and undignified in the extreme. He was surrounded by unscrupulous men, who artfully humored his notions and used him as a tool to further their own advancement. His term of office was principally passed in petty bickering, alike discreditable to himself and the nation. In him the transition from the sublime to the ridiculous was easy: he exerted his determination with equal power in crushing the bank combination, suppressing nullification, and in forcing the society of a disreputable woman upon the wives of his cabinet ministers. His personal popularity, notwithstanding, was great, and sufficed to establish for him a lasting name.

![]()

Henry W. Rugg, 1888:

EVERY MAN owes something to his fatherland. A nation has no favoritism to bestow; she gives to all her children the same virgin soil, out of which grow the weeds, or the useful plant, as individuality asserts itself in the development of character. Men may be trained in lines divergent as the poles, yet they will still possess certain characteristics common to all their countrymen; there is a vein of similarity running through every child of the same nationality, however it may be concealed in the expansion of individual life. It is this thought which is forcibly presented as the life of Andrew Jackson is reviewed. He represents a type of the American character, widely differing from the earlier Presidents of the Republic, presenting a specially marked contrast to his immediate predecessor in office, John Quincy Adams. Andrew Jackson was born amid the humblest surroundings, in a log-cabin, of a Carolina settlement, enduring privation and want, early thrown upon his own resources; while Adams had all the advantages of foreign culture, together with a college education, the influences of a refined home and intelligent friends. Both men inherited something in common from their mother country, enabling them to serve her equally well, though aided by such different resources and possessing capabilities of so opposite a nature.

The life of the seventh President of the United States began on March 15, 1767. His family was numbered among the early settlers of Waxhaw, situated near the line which divides North from South Carolina. They had a hard struggle to obtain the necessities of life, and the father, broken down by overwork and privation, died in the year 1767. The widow abandoned the desolate log-cabin, and, with her two sons, was sheltered in the family of her married sister, living near by, until after the birth of Andrew, which occurred amid the surroundings of destitution and sorrow.

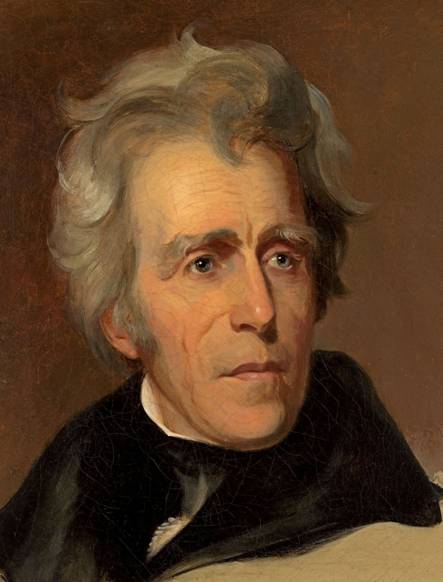

Andrew Jackson

by Ralph Eleaser Whiteside Earl, c. 1817

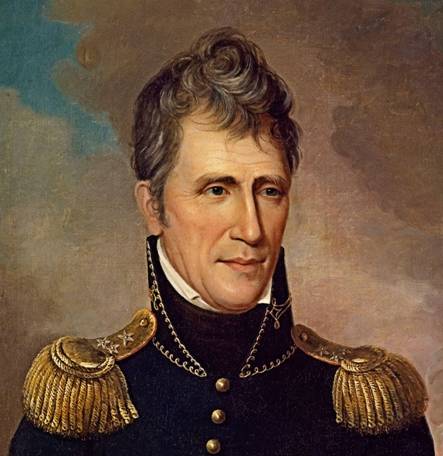

Andrew Jackson

by Charles Willson Peale, 1819

Removing at a little later period to the home of another relative, Mrs. Jackson worked early and late to maintain her boys in respectable circumstances. Andrew was sent to the rough school in the settlement, where he obtained the little education which he received. He was not an attractive boy; one could hardly expect him to be, subjected as he was to rough usage, and the influences which surrounded that hard frontier life. He was undisciplined, quick to resent a supposed injury, passionate in speech and action, showing, however, one redeeming virtue in his love for the mother who sought in her humble way for his welfare, laying the

Andrew Jackson at the Battle of

New Orleans

by Edward Percy Moran, 1910

foundation of that filial devotion and respect, which continued until her death, and gave rise, probably to his well-known chivalric opinions in regard to woman.

The courageous lad of fourteen years bore a slight part in the Revolution, fighting gallantly the Tories and troops under General Tarleton, who had invaded the Carolinas. His brother Hugh, when only eighteen years old, had lost his life at the battle of Stono; while Robert and Andrew Jackson, taken prisoners by a party of dragoons in 1781, suffered cruel treatment from their captors, the effects of which caused the death of Robert, while Andrew’s life was only saved by the extraordinary strength of his constitution. After his recovery he studied law at Salisbury, North Carolina, being admitted to the bar, and beginning a law practice in Nashville, Tennessee, where he afterwards made his home. In this vicinity, then on the borders of civilization, he made many friends, and gained reputation as a lawyer. Here he met Mrs. Rachel Robards, whom he married in the year 1791, both parties supposing that her divorce from Louis Robards had been granted. Through some technicality it was not legal and they were re-married in the year 1794. Mr. Jackson was always sensitive on this subject, thinking so highly of his wife that he resented any imputation upon her character. Their married life was exceedingly happy, though Mrs. Jackson’s position was made painful at times, and her husband annoyed, by their union becoming a cause for public discussion and scandal.

Mr. Jackson began his public career in 1797, when he was appointed to fill a vacancy in the United States Senate, where he served during the winter session of 1797-8. It was at this time, in the year 1798, that he was elected Judge of the Supreme Court of Tennessee, holding this position for a period of six years. During the next seven or eight years we find Judge Jackson enjoying a quiet home-life in his residence, the “Hermitage,” situated near Nashville. Here he found opportunities to engage in business transactions, combining them with his pursuit of farming. It was during this time that he became involved in many disputes by reason of his quick temper and hasty judgment in the difficulties arising from the conditions of society as it then existed. He fought several duels, mortally wounding his antagonist, Charles Dickenson, in one of them, and receiving severe injuries himself in another encounter.

When the War of 1812 broke out, General Jackson, who had already acquired some military skill and experience, offered his services to President Madison, pledging himself to raise a supporting force of twenty-five hundred volunteers. His offer was accepted; he became a skillful military leader, manifesting early in the campaign those qualities of endurance, strength, and will power, which earned for him the suggestive title of “Old Hickory.” His attributes made him a specially successful commander in the campaigns against the Indians – the powerful Creek and other tribes, who, under their famous chief, Tecumseh, had been won over as British allies. Jackson’s troops gained decisive victories, so that the power of these formidable tribes was forever broken.

General Jackson was appointed major-general in the regular army of the United States, May 31, 1814, and was immediately ordered to the defense of New Orleans, where the British were then

Andrew Jackson

by John Wesley Jarvis, c. 1819

concentrating their forces. Acting under his new commission, Jackson’s first move was one of peace. He succeeded in making a treaty with the Indians of Alabama and vicinity, so that they should not enter into an alliance with the enemy. It was as early as November of the year 1814, that he captured Pensacola, used by the British as a base of operations, and only a few months later, January 8, 1815, he fought and won the memorable battle of New Orleans. The defeat of the well-disciplined English troops, whose experienced commander, General Pakenham, was killed on the field of battle, was a signal victory for Jackson, made more apparent when, very quickly after the battle, the British were forced to evacuate New Orleans. The country was wild in its rejoicings over this event, and General Jackson became the Nation’s hero.

Idleness was not possible to General Jackson, so in the year 1818 – 19 he was active in the Seminole War, fighting the Indians and entering upon Spanish territory, an act for which he was much criticized. The purchase of Florida, however, put an end to the diplomatic questions suggested by the course of this impulsive commander. In the year 1821 he was appointed governor of Florida, but soon after resigned this office, not approving of the powers with which he was vested.

Again, General Jackson took his seat in the United States Senate, in 1823. The year following he was a candidate for the presidency, receiving the largest number of votes from the electoral college. There was, however, no choice, and the House of Representatives elected John Quincy Adams, February 9, 1825. General Jackson firmly believed this to be the result of collusion between Henry Clay, one of the candidates, and Mr. Adams; this thought was confirmed by the fact that Mr. Clay afterwards held office in the Cabinet of President Adams. General Jackson wrote and said many harsh, bitter words at this time, his hasty judgment leading him to utterances characteristic of his impetuous temperament – utterances made with little regard for the consequences which might ensue. One of his letters, concerning the matter, contains the following sentence: “I have been informed that Mr. Clay has been offered the office of Secretary of State, and that he will accept it; so you see the Judas of the West has closed the contract and will receive the thirty pieces of silver.”

In the fall of 1825 General Jackson resigned his seat in the Senate of the United States, returning to his home near Nashville, where he lived as a private citizen until he was elected to the presidency in 1828. The political campaign of that year was carried on in a bitterly personal manner. General Jackson was assailed with unsparing severity, but triumphantly elected, the vote in the electoral college being one hundred and seventy-eight for him, against seventy-eight for Mr. Adams. In 1832 he was re-elected by a large majority over Henry Clay, his chief competitor for the place, and served until March 4, 1837 – eight years in all.

Andrew Jackson

by Thomas Sully, before 1829

The administration of General Jackson, extending over a period when political strife was most violent, was of a notable character in many respects. It was characterized by some important acts which met with popular favor. The general conduct of foreign affairs was commended, and measures, such as the removal of Indian tribes to the more distant territories, and the settlement of the French spoliation claims, were received with a good degree of public approval. Other measures, however, were unsparingly denounced by one party, although enthusiastically commended by the other. Thus it was in regard to his course respecting the establishment and re-chartering of the United States Bank, and other matters relating to the financial policy, while much the same divided judgment was passed by the people on his appointments to and removals from office.

President Jackson’s prompt resistance of nullification, when South Carolina in 1832 proposed to withdraw from the Union, merits special recognition. He declared the United States to be a Nation, and that no state had the right to secede from the Union, and sent General Scott to South Carolina with troops and vessels of war to repress any movement of secession. His firmness and patriotism thus manifested soon brought about acquiescence to the law on the part of the dissatisfied people of South Carolina, and the danger that had appeared so threatening, was, for a time, averted. Better now than then can the American people appreciate the bold stand taken by President Jackson in this matter, and the emphasis which he put upon the words, “The Union, it must and shall be preserved.”

When public opinion puts an estimate upon character it sometimes seems that many noble qualities are left entirely out of account, just because they lead to actions not in harmony with the prevailing thought. History presents a broader view with the progress of civilization, and men like Andrew Jackson are more wisely judged, as their petty differences of opinion, their minor faults, their lack of culture or attainments sink into oblivion, while the enduring record of the positive attributes which made their influence felt upon the destiny of the Nation, grows brighter with each succeeding year.

It is good for us to remember Andrew Jackson for his honesty of purpose and life, the integrity of his nature, which betrayed itself amid the rough surroundings of the new world settlers, in the camp of the American Army, as well as during his eight years of service as the honored President of the United States. That the rough soldier, the stern leader, the passionate opponent, had yet another, more gentle side to his nature, those of his contemporaries who knew him best bore testimony. He was never

Andrew Jackson

by Ralph Eleaser Whiteside Earl, c. 1835

too busy to entertain or watch over a little child, never too careless of another’s suffering to leave a beggar in distress, never willing to listen to any adverse criticism of a woman, while he always reverenced the memory of his devoted mother, and gave to his wife the whole affection of his noble, warm heart. Quick to resent an injury, he would turn aside from any pursuit in order to confer a favor upon one of his many friends whom his personal magnetism drew towards him in an enduring association. This is a type of manhood that America does well to honor in these days when the simple republican virtues are sometimes forgotten as men celebrate the scholar and the distinguished statesman.