Click an Image for Full Size

WILLIAM HENRY HARRISON

Ninth President,

March 4, 1841 –

April 4, 1841

![]()

Franklin P. Rice, 1882:

WILLIAM HENRY HARRISON, the Ninth President, was born at Berkeley, Charles County, Virginia, February 9th, 1773. His father Benjamin Harrison, was a man of prominence, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and Governor of Virginia. William Henry received his education at Hampden-Sidney College. He entered the army in 1791, served as aide to Gen. Wayne during the Indian War, received a captain’s commission, and resigned in 1797. He was appointed Secretary of the North-west Territory and became its Delegate in Congress. He was Governor of the Territory of Indiana from 1801 to 1813, and also Superintendent of Indian affairs. The famous battle of Tippecanoe was fought November 7th, 1811, in which he gained a decisive victory over Tecumseh, and broke the power of the Indian tribes. He served with distinction during the War with Great Britain; was a member of Congress in 1816; a Senator in 1825; and in 1828 Minister to Colombia. In 1840, after an exciting contest he was elected President of the United States. He assumed the office at an age when most men seek the retirement of the grave, and his worn-out frame quickly succumbed to the over-exertion and excitement attending his resurrection into public life. He died April 4th, 1841.

Of William Henry Harrison it can be said that he was honest, simple minded and faithful to his duty. Solid or brilliant qualities he did not possess. His was the first instance of the triumph of expediency over merit in presidential nominations; and it furnished a precedent the following of which has become the rule rather than the exception. Buffoonery was an important factor to his election, and the cry of “Tippecanoe and Tyler too,” and the parading of Log Cabins with hard cider barrels and coon skins proved more effective than would have the most eminent personal qualifications.

![]()

Henry W. Rugg, 1888:

THE STATE OF Virginia has often formed a picturesque background for important events in the history of the American nation. The reader of colonial records quickly learns to associate this region with some of the most striking episodes connected with the progress of this republic, while the truth becomes apparent that many of the scenes connected with the founding of the nation were laid among the Blue Ridge Mountains or in the fertile valleys of Virginia. The subject of this sketch, William Henry Harrison, although elected from Ohio to fill the office of ninth President of the United States, was born at Berkeley, Charles County, in Virginia, February 9, 1773. His father was one of the group of intelligent and thoughtful men who were leaders in the patriotic struggles of those early days; men distinguished for ability and culture, who were prominent in the best society of Virginia at that period. To this little circle, so influential in the revolutionary times, belonged General Washington, with whom Benjamin Harrison enjoyed a confidential friendship. The elder Mr. Harrison was Governor of Virginia for several terms, and his signature was affixed to the Declaration of Independence. Thus the boy, William Henry, inherited a love for country and was early taught in the principles which ever afterwards were inseparable from his nature.

The residence of the Harrison family was a Virginia homestead, whose interior was brightened by all the evidences of a refined taste. There was the good cooking and skillful management of the numerous servants that prevailed in the best Virginia households of that day, while the exercise of a generous hospitality made the group, gathered about the blazing back logs, always a large one. William Henry Harrison was a favorite among his young associates as well as among his teachers and the older family friends. He had, as a boy, an active, enquiring mind, which gave him a fondness for books and a desire for wide information concerning men and things. He had acquired the basis of a thorough education when he entered Hampden Sidney College,

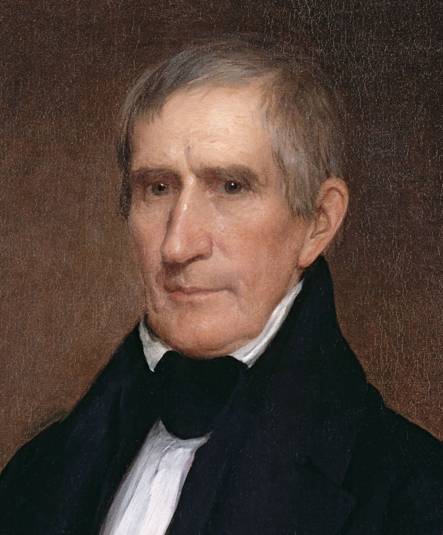

William Henry Harrison

by Rembrandt Peale, c. 1813

where he devoted himself closely to his studies, graduating therefrom when nineteen years old. During the time of his college life his father had died, so the young man, thrown somewhat upon his own responsibilities, decided to go to Philadelphia, where he could pursue to best advantage the study of medicine. Several of his father’s friends took an interest in the youthful medical student, among them his instructor, Dr. Rush, who had been an associate of the elder Harrison in signing the Declaration of Independence.

At this time, during the Presidency of Washington, the Indians on the frontier were committing the greatest outrages, and frightening by their depredations the settlers throughout the northwestern territory. These Indian tribes were powerful because of numbers and the abundant supplies and munitions of war furnished them by the British provincial officials. Young Harrison felt the patriotic ardor running through his veins as he learned of one and another of the atrocities which had been committed along the frontier, so that he abandoned his medical studies and gladly accepted the commission of ensign offered him by President Washington, who was then engaged in organizing an army against these hostile tribes. Harrison soon reported for duty to the officer in command, General St. Clair, at Fort Washington, on the Ohio River, and was at once actively engaged in the fortunes of the campaign. He speedily developed the traits of a good soldier, showed physical endurance unlooked for in so slight a frame, and won renown for courage and military skill unusual in so young a man. He received special commendation from General St. Clair, who recognized the soldierly characteristics of the youthful ensign. It was thus early in his military career that Mr. Harrison took a strong position in favor of the principles of temperance, adopting for himself the rule of total abstinence from all strong drink, a habit which he maintained to the end of his life. It was no easy matter for a young man to keep from drinking in those days of army service, when intemperance was the rule among the soldiers, and temptations were offered on every side; but Mr. Harrison was true to his own convictions of right, and could not be turned aside by any allurement which might be offered.

The services of this faithful soldier merited and soon received recognition by a promotion in the army, and, under General Wayne, Lieutenant Harrison fought efficiently in the

William Henry Harrison

by James Reid Lambdin, 1835

bloody battles which followed one another during the Indian warfare. As aide-de-camp to General Wayne, he gave proof of courage, coolness and military skill, as displayed on the field of battle. He was again promoted in 1797 to the rank of captain, and it was about this time that he became interested in and married the daughter of one of the earliest settlers on the banks of the Maumee River.

Captain Harrison resigned his commission in the army in 1797, and was appointed secretary of the northwest territory, rendering important services to the people of that newly-organized district, who elected him, in 1799, to represent them as delegate in Congress. When, in 1801, the northwest territory was divided, Mr. Harrison was appointed governor of the section organized under the name of Indiana, which then included the present States of Indiana, Wisconsin and Illinois. For a period of twelve years Governor Harrison discharged the duties of his office with notable ability and zeal. He was specially successful in his treatment of the Indians, his campaign on the frontier having given him valuable knowledge on the subject of the methods and habits of savage life. He was able to obtain for his Government vast areas of land, about sixty millions of acres, ceded in the various important treaties which he concluded with the Indians. When, in 1811, hostilities again broke out, Captain Harrison took command of the troops and was eminently successful in the memorable battle of Tippecanoe, where his army gained a signal victory over the Indians who attacked them in greatly superior forces. After this military success he was commissioned by President Madison, in 1813, as Major-General and Commander of the Northwestern Army. Again he conducted his troops to victory, winning the battle of the Thames over the British forces and their savage allies, Tecumseh, the great Indian warrior, being killed during the encounter.

In the year 1816, General Harrison was elected to Congress as Representative from the State of Ohio. He was known as an able, active, influential member; his speeches were effective and logical, while his energy gave him a well-deserved reputation for diligence in the conduct of those affairs that claimed his official attention. While in Congress he supported the resolutions censuring General Jackson for his course in the Seminole war. This somewhat reckless

William Henry Harrison

by Bass Otis, 1841

military leader had pursued his own policy with but little regard for law or courts, and, in consequence of his action in the matter, he was censured by many persons in the expression of public opinion. General Harrison, in approving of the resolutions, paid a high tribute to General Jackson’s gallantry, at the same time giving utterance to his opinion that the action of the famous military commander in disregarding civil laws ought to be disapproved.

In the year 1824 General Harrison served as one of the Presidential Electors from Ohio, casting his vote for Henry Clay, and that same year he was elected United States Senator. It was four years later, in 1828, when he was appointed Minister to the Republic of Columbia by President John Quincy Adams. Only for a brief period was he continued in this diplomatic station, for he was recalled soon after the inauguration of President Jackson. While it may not be affirmed that this action of the newly elected President was altogether due to a feeling aroused by Harrison’s support in Congress of the resolutions censuring General Jackson it is a fact that the friendly relations of the two men were never quite the same after the incident, and it seems but natural that something of personal feeling should have entered into the quick, positive call to return which President Jackson issued.

After this period of public service General Harrison returned to his comfortable home at North Bend, Ohio, where he passed a few years in the quiet pursuits which he enjoyed so much, indulging in the pleasant duties of a farmer and country gentleman. But his abilities as statesman and patriot were too generally known to allow of a private life, so that in 1836 he became candidate of the Whig party for the Presidency. He ran against Martin Van Buren, who was successful in the contest, but in 1840 Mr. Harrison was elected over the same candidate by an overwhelming majority. The canvass was a memorable one. The candidate of the Whig party was from Ohio, then a region of the Far West, and the log cabin, which became the emblem of his party, signified the prevailing thought concerning Western civilization. The campaign was most lively. With General Harrison was associated, as candidate for Vice-President, John Tyler of Virginia, so the political songs rang with the refrain of “Tippecanoe and Tyler, too,” while the hard cider, the appropriate beverage, was drank enthusiastically to the success of the “hero of Tippecanoe.”

The inauguration of President Harrison was a brilliant pageant, and was witnessed by immense throngs of the American people. The inaugural address of the President was permeated with that spirit of moderation which ruled his entire life, which controlled his actions, and which he desired his countrymen to exercise in the administration of the nation’s affairs. Judging by his former attainments and his successful statesmanship, this policy would have been carried out by President Harrison in a manner to reflect honor upon himself as upon his beloved country; but this great and good man did not long live to enjoy the exalted position to which he was called. It was only a month after his inauguration that the death of President Harrison occurred; the echoes of the animated campaign and the exultant chorus of the triumphant party still sounded through the country, and the Whigs’ rejoicing over a long-deferred victory was turned into mourning, not only for the able head of their party, but for the political situation sure to ensue. The death of President Harrison, April 4, 1841, was a great blow to

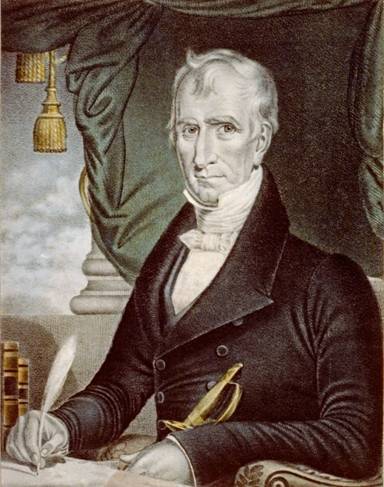

William Henry Harrison

Hand-colored Lithograph by N. Currier, 1835 - 1856

the American nation, and his funeral awakened intense interest throughout the country, following, as it did, so soon after the imposing ceremonies connected with his inauguration.

There was a simple dignity in the character and life of President Harrison that endears his memory to every true heart wherever virtue and honest worth are acknowledged as sovereign factors in the elevation of humanity to the achievement of its highest ideals. America comes more and more to realize what great men have been a part of her history, what a debt of gratitude she owes to those who, in differing degrees, have rendered such service to establish her upon the solid foundation which to-day she occupies. These men who have stood for something in their day, compare favorably with the leaders and statesmen of other lands and times; viewed from an impartial position each has played well his part in the drama of America’s establishment. The different talents, the varied acquirements have been used to make the Nation what it is, and, though men do not judge alike to-day or ever, they are more willing in this nineteenth century, as it seems, to value whatever is good, whatever makes for the prosperity of a people, even though the qualities displayed may not be in accordance with their own thought or judgment. So the just estimate of President Harrison makes prominent those principles of moderation, that temperance in all things, that well-balanced mind, those qualities of a successful military leader which were sufficient to distinguish this man above his fellows and render him capable of valuable service in behalf of his country’s advancement. His was a consistent, manly career, a life overflowing with benevolence and justice towards all, a respect for the rights of every human being, however degraded its condition. He was American to the centre of his personality; rejoiced in all her prosperity, advocating no reckless measures while he advised that moderation which the impetuous sons of the new Republic were sometimes slow to heed. Such men as William Henry Harrison leave better records for future generations to admire than the more brilliant heroes of popular fancy, whose reputation, easily gained, is as easily forgotten in the progress of time.

![]()

William Henry Harrison

Hand-colored Lithograph by N. Currier