Click an Image for Full Size

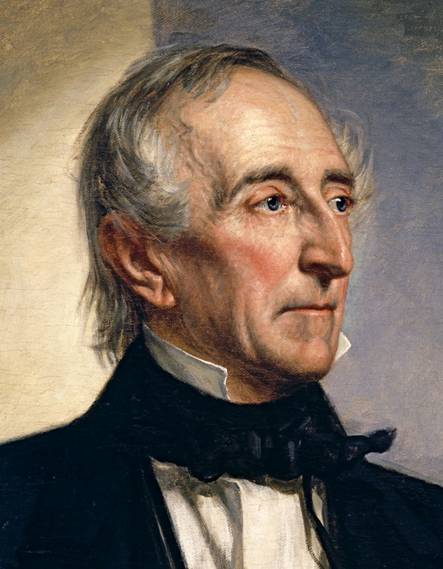

JOHN TYLER

Tenth President,

April 4, 1841 – March 4,

1845

![]()

Franklin P. Rice, 1882:

JOHN TYLER, the Tenth President of the United States, was born in Charles-City County, Virginia, March 29th, 1790. He graduated at William and Mary College, studied law and soon entered upon a large practice. In 1811 he was elected to the State Legislature, and in 1816 to Congress. He was Governor of Virginia in 1825, and Senator in 1827. On account of a difference with President Jackson he resigned his seat in 1836. He was elected Vice President in 1840, and became President by the death of Harrison in 1841. He was President of the Peace Convention in 1861, and a member of the Confederate Congress, and died a rebel, January 17th, 1862.

Mr. Tyler’s political course appears to have been changeable and erratic. He supported the measures of Jefferson and Madison, and later those of General Jackson; but he abandoned the latter on the removal of the deposits and joined the Whig Party. After he became President his Democratic tendencies were apparent, but he attempted to please both parties and form by this method, as he hoped, a universal Tyler party. The pet project of the Whigs was the re-establishment of the national bank, and although Tyler at first favored the scheme, he vetoed one bill that did not suit him and another one that did; and he was soon in an open quarrel with those to whom he was indebted for his office. He was deserted by all his former political friends, and at the end of his term stood alone without a follower. At the Peace Convention he professed great attachment for the Union, but on his return home exerted his influence to destroy it.

![]()

Henry W. Rugg, 1888:

IT IS good for the American people to remember that their leaders have frequently been men of lowly origin, that the log cabin fitly represents the humble birth-place of some heroic ones destined to fill highest offices and win their countrymen’s respectful homage. This truth has been so much dwelt upon that many doubt the genius of a man, unless his early surroundings were those of homespun inheritance, if not of actual poverty. While paying all honor to any who have made for themselves a name, coming from obscurity into the full light of a national reputation, there is much to commemorate in other prominent lives which have been developed by the influences of a cultured home, surrounded by the advantages of wealth and refinement. Some of the presidents of the United States were thus “born to the purple,” tracing their ancestry to distinguished men, and belonging to families of high social position. One of these favored ones was John Tyler, born March 29, 1790, at Greenway, Charles City, County of Virginia.

The tenth Chief Magistrate of the nation was a precocious lad, devoting himself so assiduously to his studies that he entered William and Mary College well prepared, at an early age, graduating from that institution when but seventeen years old. He studied law for a time under Edmund Randolph, and afterwards with his father, both of whom were distinguished advocates, well known and highly esteemed throughout Virginia. He rapidly acquired distinction in the profession, and also gained a reputation for his knowledge of political matters, so that when he had but just attained his majority he was elected a member of the Virginia House of Delegates. Mr. Tyler, in December of the year 1811, took his seat in the legislature, where his abilities as a ready debater and eloquent speaker were quickly recognized. He served in this body for five successive years to the satisfaction of his constituents, who retained him in his seat by large majorities at each election.

The military services of Mr. Tyler were not of great importance, although, at the time when British forces were

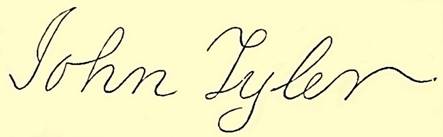

John Tyler

by James Reid Lambdin, 1841

threatening Norfolk and Richmond, he raised a company of soldiers, of which he was placed in command, and with which he subsequently served in the Fifty-Second Regiment, stationed at Williamsburg.

When but twenty-six years old, in 1816, Mr. Tyler was elected to Congress, soon becoming conspicuous for his skill in debate, as well as for his familiarity with the important questions discussed. He won distinction during his several terms of service; he was an intense worker, applied himself diligently to master the subjects of legislation, that he might best discharge the duties which devolved upon him. By close attention to official labors his health became affected, forcing him to resign his place in Congress. He returned to his home in Charles City County, and, rapidly regaining his usual health, entered with renewed ardor upon the practice of his profession. Soon after he again accepted an election to the legislature, exerting in that body a most pronounced influence.

Mr. Tyler was elected Governor of Virginia in 1825, and re-elected the following year, almost unanimously. His administration of this important office was generally acceptable. He showed rare skill in composing sectional differences and assuaging the bitterness of party animosity, while he sought to stimulate the growth and development of his native state. At this time, when his popularity was greatest, he was elected to the United States Senate, succeeding Mr. John Randolph, the regular candidate of the Democratic party for re-election. Governor Tyler’s victory, under these circumstances, was indeed a proof of the general esteem in which he was then held by the people of Virginia.

On the third of December, 1827, Mr. Tyler assumed the duties of Senator, at once allying himself with the opposers of President Adams’ administration, notwithstanding the support he had received in the Virginia Legislature from its friends. He was a strict constructionist of the Constitution, disposed to limit the powers of the general government, and to sustain the doctrine of state rights. He voted against the tariff bill of 1828, and most of the measures for internal improvements which came under consideration about this time. When General Jackson succeeded to the presidency, Senator Tyler gave the new administration his support, although often pursuing an independent, not to say erratic course. He was in sympathy with Mr. Calhoun and the nullifiers of South Carolina, justifying their course on the extreme ground of state rights, while he was antagonistic to the efficient and patriotic course of President Jackson in seeking to compel the people of South Carolina to obey the laws. He gave vigorous opposition to the force bill, designed to provide for the collection of the revenue in the disaffected region, and vesting extraordinary powers in the President. At a later period, however, he used his influence in favor of the compromise and pacification measures introduced into the senate by his personal friend, Mr. Clay.

John Tyler

by George P. A. Healy, 1842

Senator Tyler was re-elected to the Senate for six years, dating from March 4, 1833. Though nominally identified with, and owing his election to the Democratic party, he severed himself from such party affiliations by voting to sustain the resolutions introduced by Mr. Clay in 1834, censuring President Jackson for the removal of the public deposits, holding that he had exceeded his rightful authority in so doing. The Virginia legislature instructed the senators from that State, in February 1836, to vote in favor of expunging from the Senate journal the resolutions censuring President Jackson. Senator Tyler refused to obey these instructions, but held that it was not right for him to retain his seat after so refusing; therefore, he resigned his senatorship, three years only of his term having expired. His conduct in this matter was generally commended and he lost nothing of reputation by making his action in this respect conform with his previous record.

After his retirement to private life, in February, 1836, he again resumed the practice of law in Williamsburg, where he had removed his family two or three years previously. In the presidential campaign of 1836, the name of Mr. Tyler was associated with that of General Harrison on the ticket supported by the Whig party in some of the states; but Maryland was the only State which voted for Harrison that also gave its electoral vote to Mr. Tyler for Vice-President. He received, however, other votes from the state rights party of the South and West, which opposed Mr. Van Buren, so that in all he obtained forty-seven electoral votes for the office named.

At a convention of the Whig party held in 1839 at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, to nominate candidates for President and Vice-President, Mr. Tyler, delegate from Virginia, zealously supported Mr. Clay for the first place. General Harrison, however, was nominated; then, as a sort of propitiation to the friends of the defeated candidate, Mr. Tyler was selected as candidate for the office of Vice-President. This position was not thought to be specially important, no President having died in office; the idea of Mr. Tyler’s ever succeeding to the presidency was not taken into account. Had it been, the choice of the convention would probably have fallen on some one more thoroughly committed to the policy of the Whig party, one on whom a greater confidence could be placed for his reliability.

The exciting campaign of 1840 has elsewhere been referred to; it is sufficient in this connection to state that it resulted in the triumphant election of General Harrison as President and Mr. Tyler as Vice-President. President Harrison died one month after his inauguration; Mr. Tyler, in accordance with the provisions of the constitution, succeeded to the presidency, April 4, 1841. Two days later he took the oath of office as President and entered upon the responsible duties of that position. His course during the three years and eleven months of his presidential service greatly disappointed the political leaders of the country and almost completely estranged him from his former friends. It has well been said of him that “he lost the respect of the party by which he was elected without gaining that of their political opponents.” He

John Tyler

Hand-colored Lithograph by Currier & Ives, 1835 - 1856

vetoed various measures supported by the party to which he owed his election and for the most part declined to act with the majority in Congress. His successive vetoes of bills to incorporate a national bank caused great indignation. He was accused of bad faith, of working for a re-nomination which he thought he might secure from the opposition, with whom he was most in sympathy, though he was not much liked or greatly trusted by them. His administration was characterized by several important acts and measures, one of them being the settlement of the difficulties with Great Britain, by the adjustment of the northeastern boundary between Canada and the United States. Another important negotiation was the treaty with China, while the annexation of the republic of Texas awakened bitter opposition, partly because of the expenditure of money called for in assuming the Texas debt of $7,500,000, partly on account of the prevailing idea at the North that the new acquisition of territory was “to uphold the interests of slavery, extend its influence, and secure its permanent duration.”

It was probably a great relief to President Tyler, whose administration had been so generally unacceptable to the country, when he could retire from office and enjoy his pleasant home at Sherwood Forest, Charles City County, Virginia, where he passed the years of his age in comfort, until the beginning of the Civil War in 1861. Then his old ideas of state rights and his advocacy of Mr. Calhoun’s doctrines led him to join the Confederates. He was afterwards chosen a member of the Confederate Congress, but his death occurred at Richmond, January 18, 1862, and he never served in that body.

President Tyler was twice married, first to Miss Letitia Christian, who died in 1842, and was an invalid through much of her life. During his presidency, Mr. Tyler married Miss Gardiner of New York, whose father was killed by an explosion which occurred on the steamer Princeton, when Commodore Stockton was giving an entertainment to the government officials, the President being on board at the time, and two members of his Cabinet losing their lives by the disaster. The second Mrs. Tyler was a woman of distinguished appearance, who assumed more of the outward dignities of her position than any of her predecessors in the White House.

History is truth itself, but the records of nations are not history till time has separated the wheat from the chaff, until the years have weighed men’s actions in an even balance, adjusting rightly those influences and currents of thought not taken into account by a hasty judgment or the sentiment of the hour. While his best friend could hardly justify President Tyler for his action in some of the important issues of the day, his greatest enemy would acknowledge the many praiseworthy characteristics of his public and private life. He was a man of the world in the best sense of the phrase; educated, not only in books, but in the school of experience. He was a firm friend to the small circle of intimates whom he loved, while he displayed eloquence and brilliancy, both in his familiar conversation and in his public speeches. His life was beset with

As

mentioned on the previous page and illustrated on this

hand-colored lithograph by N. Currier, 1844:

“Awful explosion of the ‘peace-maker’ on board the U. S.

Steam Frigate, Princeton, on Wednesday, 28th Feby. 1844.”

Besides David Gardiner, father of Julia Gardiner,

also killed in the explosion were

Secretary of State Abel Upshur,

Secretary of the Navy Thomas Gilmer,

Captain Beverly Kennon, the Chief of the Bureau of Construction and

Repair,

Virgil Maxcy of Maryland,

and a slave named Armistead.

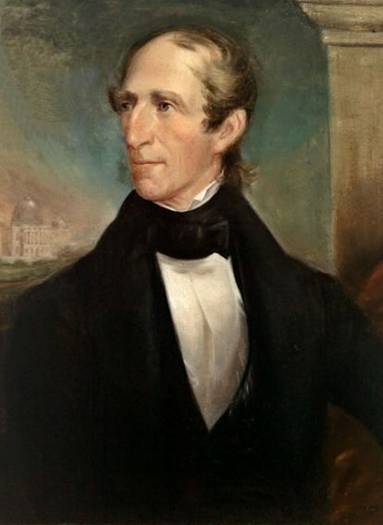

John Tyler

by Hart, c. 1841 - 1845

many trials; he forfeited in later years the public confidence which he had held to so great a degree during his earlier political career, and he was tried in ways as unusual as they were severe. He would have been censured, whatever his course, even though it followed the best promptings of his nature, for his position, surrounded by difficulties, allowed of no popular way to overcome the murmurs and dissatisfaction incident to his administration. The world, very apt to give publicity to the failings of great men, will slowly learn to remember President Tyler for the virtues he displayed, those excellent traits of character which ought to do something towards blotting out the record of the many errors he so prominently exhibited during the later years of his public service.

![]()

John Tyler

by Thomas Wilcocks Sully, Jr.