Click an Image for Full Size

ABRAHAM LINCOLN

Sixteenth President,

March 4, 1861 – April 15, 1865

![]()

Franklin P. Rice, 1882:

ABRAHAM LINCOLN, the Sixteenth President of the United States, was born in Hardin County, Kentucky, on the 12th of February, 1809. He received about a year’s schooling, and worked for some time as a hired hand on a Mississippi River flat-boat. In 1830, he removed to Illinois, studied law, and was admitted to practice in 1836. He was captain of a company in the Black Hawk War. His law practice was successful, and he took a prominent part in the politics of Illinois on the side of the Whigs. He served in the Legislature from 1834 to 1841, and was a member of Congress from 1847 to 1849. In 1858, as candidate for Senator in opposition to Stephen A. Douglas, he engaged in a series of remarkable debates with that personage; and the ability displayed in this canvass led to his nomination for the Presidency in 1860. He received the vote of all the Free States except New Jersey. When he assumed his office, he found the powers of the government crippled, its energies restricted, and a large section in open rebellion. His administration was passed in a fierce struggle to maintain the integrity of the Union, and he finally fell a martyr to the cause. He was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth, and died on the 15th of April, 1865.

Abraham Lincoln was one of the best representatives of American Democracy. He rose from obscurity to the highest position, and enrolled his name with those of the benefactors of mankind. The qualities of his mind were solid rather than brilliant; he had a large heart, and a shrewd if not cultivated understanding. Benevolence was a distinguishing trait. His manners had little of polish, and his appearance was uncouth, and often excited ridicule; yet there were occasions when his efforts reached the point of sublimity. The Emancipation Proclamation was the great act of his life, and established the principle for which he died. He occupies a place in the hearts of the American People second only to that of Washington.

![]()

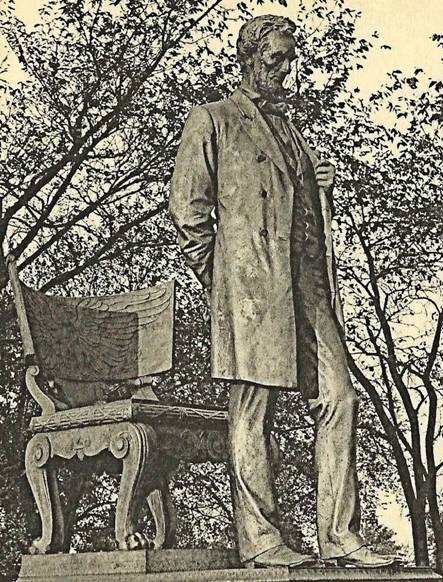

Henry W. Rugg, 1888:

BETTER THAN written description is that statue standing in Lincoln Park, Chicago, to indicate the true expression of a life, familiar in its details to the American people, yet a character whose depths were never sounded in any study of its many-sided development. The bronze figure of Abraham Lincoln not only reproduces his physical attributes, but the artist has brought out, in a right conception of what the statue should reveal, the greatness of the man, suggesting, by the expression and the attitude, that personality which a biography sometimes fails to present. In the sympathetic treatment of so difficult a subject, the sculptor has produced an instantaneous picture, a composite representation, embodying the uncouth lad, the diligent surveyor, the useful lawyer, the skilled leader of debate, the Nation’s Chief Magistrate, and its martyred hero, - while above all shines the glory of simple, honest virtues, the goodness as well as the greatness that was his. Thus the statue emphasizes the biographical teachings of an individuality, potential not only by reason of its opportunities, but from its inherent moral balance; that wonderful spirit, enveloped in so rough an exterior, which expanded, in dignity and simplicity, among all the rude and unfriendly influences to which the life of Lincoln was subjected.

Diligent search has revealed but little concerning the life of Thomas Lincoln, the father of Abraham, the fragments of biography, however, being sufficient to indicate the toil and suffering by which his life was bounded. In the midst of the dense forest on Nolin Creek, of what is now La Rue County, Kentucky, Thomas Lincoln and his young wife built a home, a rude log cabin, where their son Abraham was born February 12, 1809.

Photograph of the statue referred

to on the previous page.

Abraham Lincoln by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1887,

in Chicago’s Lincoln Park as pictured on a postcard c. 1910

The boyhood of Lincoln offers an inviting field, but it must not be enlarged upon within the limits of this sketch. It included an early childhood spent in the backwoods; an immigration with his family to Indiana; the loss of a dearly-loved mother; the advent of a step-mother who was truly a parent to the neglected children; a limited education in books, but the using of every opportunity for study, so that he learned to read and write; another removal of the family to Illinois, and the rough, laboring life of a new frontier settlement. Mrs. Lincoln’s testimony that “Abe” was a good boy, was in harmony with the general tribute paid to his generous, amiable qualities, his defense of weaker, down-trodden humanity, of cruelly-used animals, his straightforwardness, his determined will, and his energy as displayed in those boyhood years passed in poverty and hard work.

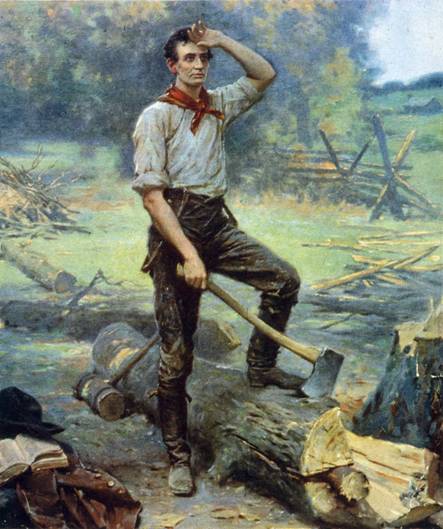

Having attained his majority and aided in the establishment of a new home for his parents, the young man went forth to seek occupation and begin the shaping of a career which in its progress was to be invested with a marvellous power and attractiveness. He first engaged himself as a laborer to work on a farm near his father’s residence. There he was employed a part of his time in building fences, so that in the political campaigns of late years he was frequently designated as the “rail-splitter” of Illinois. Then he went to Springfield, the shire town of Sangamon County, and since made the capital of Illinois, where he wrought in the construction of a large flatboat, which he helped to guide down the Sangamon, Illinois, and Mississippi rivers to New Orleans. Returning from this trip, he worked in a country store at New Salem, Illinois, gaining the confidence of the people, who quickly discerned his abilities and manly work. In 1832, at the breaking out of the Black Hawk War, young Lincoln promptly volunteered, and was chosen to be captain of the companies raised in Sangamon County. While he did not participate in any battle, he yet bore the hardships of the three months’ campaign in so brave and uncomplaining a way that he returned to New Salem with his popularity deservedly augmented. At this period, besides performing the duties devolving upon him, he was studying surveying, becoming so well fitted for his work that in 1838 he was appointed a deputy of the county surveyor.

Abraham Lincoln “The Railsplitter”

by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, 1909

Mr. Lincoln’s political career may be said to date from the year 1834, when he was elected to the Illinois Legislature. He belonged to the Henry Clay school of politics, and was in sympathy with the general policy of the Whig party. His legislative course, which lasted through four successive terms, was marked by energy and ability, united with an earnest purpose to maintain the rights of

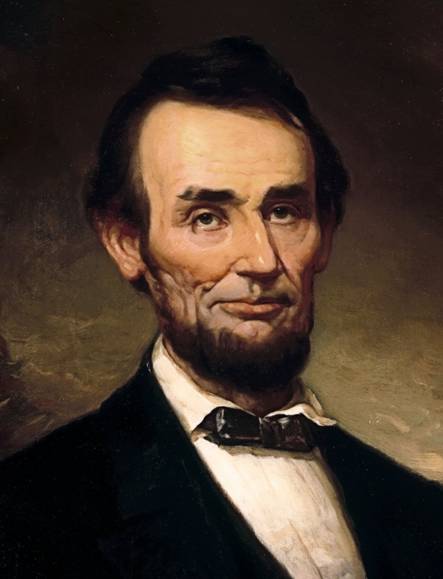

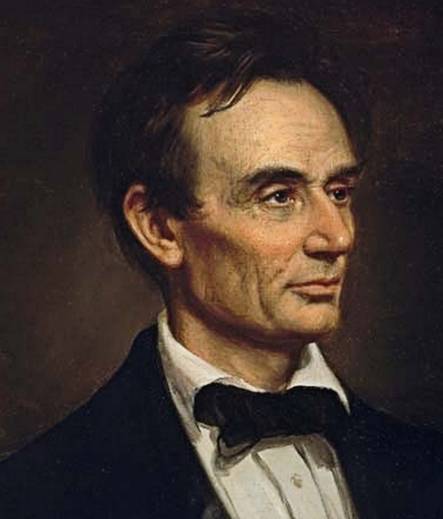

Abraham Lincoln

by George P. A. Healy, 1860

the poor and oppressed, and do exact justice to all classes. About the time of his first election, Mr. Lincoln began to pursue a course of reading, with a view of entering the legal profession. He was admitted to the bar in 1836, and the next year removed to Springfield, where he was associated with his friend and adviser, Mr. John T. Stuart, in a practice that soon became extensive and lucrative. Mr. Lincoln achieved success in the practice of law,

“Hon. Abraham Lincoln, Our Next

President”

Hand-colored Lithograph by Currier & Ives, 1860

especially in his conduct of cases before juries. He was eloquent and persuasive in speech, logical and convincing, yet noted for his fairness in the treatment of an opponent. His integrity was never questioned. His entire faithfulness to a cause or principle which he had espoused was always conceded. He won his way slowly, but surely, to a prominent place, being ranked as an upright, hard-working, capable lawyer, in whose hands the most important interests might be safely reposed. Although giving the most of his time to his law practice, he still retained an active interest in local politics. In 1846 he was elected to Congress and served one term.

The abrogation of the Missouri compromise in 1854 deeply affected Mr. Lincoln, and from that time forward he made frequent and strong expressions of his views on the subject of slavery. He became identified with the Republican party at its formation, taking, as of right, a place among its foremost leaders. In 1858, when the senatorial term of Mr. Douglas was near its close, Mr. Lincoln was put forward for the succession. In accordance with a general feeling, the two candidates arranged for a public discussion, which excited great attention throughout the country, and did much to enhance the reputation of Mr. Lincoln. He did not succeed in obtaining the senatorship, although a majority of the popular vote was in his favor, but he attained distinction by his method of treating the slavery question, going to the very heart of this disturbing issue, and dealing with the moral element. He was not an abolitionist; he was not inclined to disturb slavery in any rights that it might have under the Constitution in the States where it existed, but he boldly opposed its further encroachments. He had the clear vision to see what the issue would be. Thus he declared in one of his addresses in 1858: “A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this Government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved - I do not expect the house to fall – but I do expect it will cease to be divided.”

As the time drew near for the holding of the Republican Convention to nominate candidates respectively for the offices of President and Vice-President, the name of Mr. Lincoln was sometimes mentioned for one or the other place. The skill which he had shown in his debates with Senator Douglas was generally conceded, and yet he was not regarded with that measure of general favor accorded to Mr. Seward and others who had been largely instrumental in the formation of the Republican party. In the early part of 1860 Mr. Lincoln visited the East, speaking in New York and

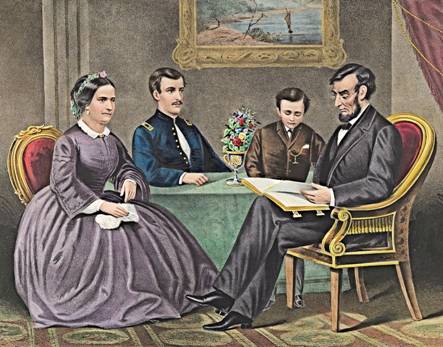

“Lincoln at Home” (After G.

Thomas)

Mary Todd Lincoln, Robert Todd Lincoln

Thomas “Tad” Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln

Hand-colored Lithograph by Currier & Ives, 1867

elsewhere with so much of intellectual and moral force as to command special attention. Thenceforth he became more widely known, and a much higher estimate was put upon his powers. It was hardly thought possible, however, that he could secure the nomination for the Presidency at the hands of the Convention which met in Chicago May 16, 1860; but on the third ballot he received more votes than were given for all his distinguished competitors, and under the pressure of an intense feeling of enthusiasm his nomination was made unanimous.

Then followed a bitter political contest, resulting in the election of Mr. Lincoln, who received 180 electoral votes, the remaining 123 being divided among the opposing candidates. During all the heated canvass, and the threatening days following his election, Mr. Lincoln bore himself with composure, making

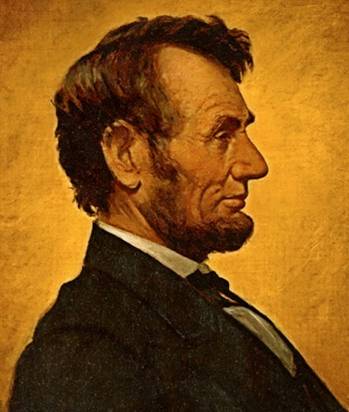

Abraham Lincoln by William

Willard, 1864

based on a photograph by Anthony Berger, Feb. 9, 1864

expression, however, not infrequently, of the resolute fibre of which his nature was formed. His letters, written at the time, show how far-seeing his vision was, and how quick and strong his impulses of patriotic devotion. Possessed of a deeply religious nature, he had a firm reliance upon Divine Providence, and believed that thus he was to be led and upheld in the arduous path of official duty. Preserved from dangers of one sort and another, Mr. Lincoln was duly inaugurated as the Chief Magistrate of the Nation. His inaugural address, while it declared “the Union perpetual and all acts of secession void,” was moderate in tone – even conciliatory towards the seceding States. But the South would not be propitiated; the bombardment and capture of Fort Sumter quickly

“The Peacemakers” by George P. A.

Healy, c. 1868

General Sherman, General Grant, President Lincoln,

and Admiral Porter aboard the “River Queen” March 27-28, 1865

followed Mr. Lincoln’s accession to power, and in a few weeks from the time of his inauguration he found himself involved in all the hard, trying conditions of a civil war – a terrible and prolonged contest, which extended over the whole of the first term of his administration, and tested him as rarely any other man was ever tried in the place of exalted leadership.

As the war progressed he had to pass upon perplexing questions connected with slavery. It seemed to some of his friends that he was over-cautious, and did not quickly enough seize the opportunity of profiting by the help of the enslaved population of the seceding States. He would not allow his commanders in the field to issue proclamations declaring freedom to the slaves. He was disposed at the first to compensate the States which would adopt a plan for the gradual and voluntary abolition of slavery; but he was watchful of events and of public opinion, and at the right time he issued the proclamation of emancipation, which, being sustained by the force of arms and subsequent legislation, resulted in the removal of slavery from the Republic.

The unexpected prolongation of the war, the vast expense of treasure and life by which it was carried on, together with political complications and clashing material interests, caused much criticism of the President and his administration. He was very patient under the burden of care and responsibility, and the added load of harsh, mistaken judgment often laid upon him. The great majority of the loyal people were in sympathy with him and rallied to his support, so that he was triumphantly elected to a second term, upon which he entered just as the war was drawing to a close. General Lee surrendered to General Grant April 9, 1865, and this was practically the end of the war. Now that victory was assured to the national government, the hope of President Lincoln was to do a blessed work of reconstruction, building anew the shattered fabrics of seceding States and so causing the restored Union to stand fair and strong. His was the great heart to do this work “with malice toward none, with charity for all.” This purpose he was not to realize. His mortal mission was accomplished. He died April 15, 1865, from the effects of an assassin’s bullet, honored and mourned by the great body of the American people.

And so this noble, true soul, this strong-minded, great-hearted man passed hence to his reward. His place is assured among the illustrious leaders of the Republic. He represents democracy in its finest instincts. He is a grand, attractive model for individual character and for national life. It is a suggestive picture of the honored, martyred Lincoln which Mr. Lowell draws: “I have seen the wisest statesman and most pregnant speaker of the generation, a man of humble birth and ungainly manners, of little culture beyond what his own genius supplied, become more absolute in power than any monarch of modern times, through the reverence of his country-men for his honesty, his wisdom, his sincerity, his faith in God and man, and the nobly humane simplicity of his character.”

![]()

by William F. Cogswell, 1869