Click an Image for Full Size

JAMES BUCHANAN

Fifteenth President,

March 4, 1857

– March 4, 1861

![]()

Franklin P. Rice, 1882:

JAMES BUCHANAN, the Fifteenth President of the United States, was born in Franklin County, Pennsylvania, April 23d, 1791. He graduated at Dickinson College in 1809, and was admitted to the bar in 1812. In a few years he acquired a competency and retired from practice. He served in Congress from 1821 to 1831, when he was appointed Minister to Russia by General Jackson, where he remained two years. He was a Senator from 1834 to 1845, and Secretary of State under President Polk. In 1853 he was appointed Minister to England, and was a party to the Ostend Manifesto. He was nominated for the Presidency in 1856. There are reasons for the belief that a fair vote would have given the office to John C. Fremont; but according to the returns Buchanan was elected. He selected for his cabinet a number of the most unprincipled of the disunionists – men who were afterwards notorious for their villainies – and with the aid of this party of worthies, he carried the nation to the verge of destruction. The President contemplated with indifference and helplessness the acts of the conspirators, until, appalled by the ruin they had wrought, he made near the end of his term, a feeble effort to retrieve the power of the government. After his retirement he published a vindicatory volume. His death occurred at Wheatland on the first of June, 1868.

James Buchanan passed nearly forty years of his life in public service. He was during that time, a prominent personage before the country, and occupied many places of honor and trust. Circumstances rather than talents were responsible for this, for his abilities were not of a high order. He yielded himself to the influence of the worst elements in American politics, and forfeited his character and independence for the sake of position. He was weak rather than wicked, and his desire for office overcame every other consideration.

![]()

Henry W. Rugg, 1888:

NATURE PLEASES us most when she furnishes a background for historical or biographical incidents; when there is associated with the grandeur of her mountains or the quiet loveliness of her valleys, some human interest, leading to that “proper study of mankind,” as connected with the gracious influences of the outward world. When the boyhood of James Buchanan, fifteenth President of the United States, is recalled, there arises a thought of the lofty Alleghany Mountains, whose peaks overshadowed the secluded farm-house, situated in a little settlement of Franklin County, Pennsylvania, where he was born April 23, 1791. As soon as he was allowed to explore the wooded region near his home he spent much of his time out of doors, learning in his childhood days to appreciate the beauties which Nature so lavishly displays for her admirers. His mother, having an artistic nature, an inherent love for the beautiful, encouraged and educated her son’s taste for the refinements of life, although in that simple frontier home it was not easy to acquire luxuries or receive the benefits of books and cultured society. About the year 1800 these thoughtful parents removed their family to the town of Mercersburg, that they might secure more of educational and social advantages for their son, an intelligent, interesting, somewhat precocious lad. Thus early separated from his beloved mountains and the forests where the settler’s axe had but recently resounded, he never forgot, during the varied experiences of his after life, the surroundings of his early home, the intercourse with Nature which distinguished his boyhood days.

Having made rapid progress in his studies, James Buchanan entered Dickenson College, at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and graduated with honor from that institution when he was eighteen years old. At once he began the study of law, was admitted to the bar in 1812, and established his legal practice in the city of Lancaster, rapidly gaining reputation as an able advocate, in spite of his youth and inexperience. Important cases were entrusted to his

James Buchanan

by Jacob Eichholtz, 1834

care, and his treatment of them more than justified expectation. “At the age of thirty years,” says one of his biographers, “it was generally admitted that he stood at the head of the bar, and there was no lawyer in the State who had a more extensive or lucrative practice.”

When, in 1820, he entered Congress, where he remained for five successive terms, he was obliged to relinquish a large proportion of his practice in order to perform the services devolving upon his official position. As a member of the State Legislature, in 1814, he had urged the vigorous prosecution of the war of 1812, and while originally a Federalist, his opinions changed somewhat, so that he came to advocate the Jeffersonian idea of a strict construction of the powers granted the general government. Naturally he allied himself with the Republican, afterwards the Democratic party, taking ground against a protective tariff, and in opposition to the general policy of President John Quincy Adams, while he warmly espoused the measures advocated by General Jackson. At the completion of his fifth term he retired from Congress, having earned a reputation for a sound judgment, a wisely-directed activity, made apparent in all labors for the State or Nation which he had been called upon to perform.

Appointed Minister Plenipotentiary to St. Petersburg, in the year 1832, Mr. Buchanan was able to negotiate, in his representative capacity, a commercial treaty, securing to the United States important privileges in the Baltic and the Black Sea. On his return to this country the Pennsylvania Legislature elected him to a seat in the United States Senate. Among such representative men as Webster, Clay, Calhoun and Wright, his influence was yet felt, and he gained a position well to the front, among the foremost leaders of his party. In matters where the interests of slavery were involved he was generally inclined to favor the demands of the South, although it is to be remembered to his credit that he supported President Jackson in his course against nullification. Mr. Buchanan took the position that Congress had no power to legislate on slavery, but evidently he was willing to perpetuate and extend the system, and to bring Congressional influence to bear upon such extension.

At the period of President Van Buren’s administration, Mr. Buchanan gave his earnest advocacy to the measures proposed by the National Executive, notably, that important action respecting the establishment of an independent treasury. In 1845, he accepted the invitation of President Polk to enter his Cabinet, where, as Secretary of State, his abilities found ample and congenial scope. With the retirement of Mr. Polk from the Presidency there came to Mr. Buchanan a welcome relief from official duties and the activities of political interests. After enjoying for several years the life of a private citizen, he was summoned therefrom by President Pierce, who appointed him Minister to Great Britain. While abroad in the fulfillment of his mission, he joined Messrs. Mason and Soule, Ministers respectively to France and Spain, in a conference at

James Buchanan

by John Henry Brown, 1851

Ostend, which resulted in the issue of a manifesto, proposing the acquisition of Cuba, by purchase or otherwise. This Ostend Manifesto, which caused great excitement in the United States and Europe, reflected but little honor upon Mr. Buchanan, the originator of the movement.

Upon returning to his native land, in 1856, Mr. Buchanan became the candidate of the Democratic party for the Presidency. He was elected over ex-President Fillmore, candidate of the American party, and John C. Fremont, supported by the newly formed Republican organization, to which were attached many members of the Whig and Free Soil parties.

In many respects President Buchanan was eminently fitted for the high position to which he was called by the American people. He had native and acquired ability, a large and varied experience, and was familiar with all departments of the public service. He was confronted, however, by unusual difficulties, so that he was tested to an extreme degree. His administration was unique and eventful from its beginning to its exciting close. A condition of affairs amounting almost to war existed for the greater part of the time, and new perils were constantly appearing. There was an inheritance of the Kansas-Nebraska imbroglio, with other questions of a troublesome character. Soon followed the Dred Scott Decision, which greatly intensified the anti-slavery feeling by declaring the right of slave-holders to take their slaves into any State and hold them there as such, despite any local law to the contrary. This decision, regarded as changing slavery from a local to a national institution, acted as a new stimulus to the agitation which President Buchanan vainly hoped to quiet.

The famous raid of John Brown, in 1859, produced the greatest excitement throughout the country. The leader was a brave, conscientious man, of noble impulses, but fanatical to the extreme regarding slavery. His ambition was to be a liberator, and his raid at Harper’s Ferry was designed to force the issue and bring on a general uprising of the slaves. It was impossible that such a movement as that which he inaugurated should succeed. He and his associates were soon captured by a United States military force, and the brave leader paid the penalty of his mistaken ardor with his life. The movement, however, and all that went with it and followed, tended to widen the breach between the North and the

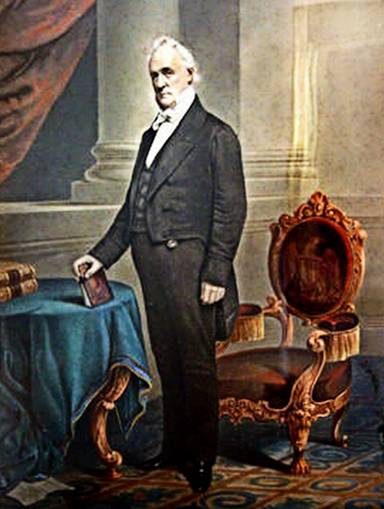

James Buchanan

Hand-colored Lithograph by N. Currier, c. 1856

South, and augment the difficulties of Mr. Buchanan, who was seeking to do a work of pacification, for which the time had passed.

There were other troubles with which the President had to deal, besides those directly relating to slavery. The Walker filibustering expeditions gave him much annoyance; but these movements terminated with the capture of Walker, who was tried and executed by the military authorities of Honduras. There were likewise old questions of a complicated nature pertaining to foreign affairs; and, in his dealing with these issues, President Buchanan was remarkably fortunate. He caused the English government to abandon its alleged right to search American ships – a claim, the attempted enforcement of which caused the war of 1812. This was a most satisfactory settlement of a question that had been one of frequent irritation between the two countries.

As the administration of President Buchanan approached its close, the aspect of affairs grew more threatening, the South being determined to withdraw from the Union and establish a separate government. When the Presidential election of 1860, which resulted in the choice of Mr. Lincoln, was decided, there was no longer hesitancy in going forward with the movements of secession. Forts were seized, public property appropriated, and various measures instituted and actively entered upon which were intended to result in the disruption of the Union. The President was halting and irresolute at this critical juncture. He was neither bold nor prompt enough in his action to meet the emergency. He hesitated, and counseled inactivity when he should have moved forward to check the attempted movement of disunion.

President Buchanan declared in his address to Congress, of December, 1860, that no State had the right to secede from the Union; but he doubted his own powers to coerce a sovereign State, though he thought he could protect the Federal forts and prevent their capture. He tried to do this at the last, but was unable to keep Forts Sumter and Moultrie in Charleston Harbor from passing into Confederate hands. He did not believe that the Constitution gave him the power which he would like to use against secession. He was not cast in heroic mould, and could not deal with the impending crisis as a bolder man, one not carrying so great a weight of years, and by nature less conservative, would have done. He did not wish to bring on civil war, albeit the very course he took may have tended to that result. No doubt he misapprehended the situation and showed a lack of firmness, but there is no proof that he was at heart unpatriotic, or that consciously he wrought in aid of secession. After the organization of the Confederacy he still hoped that it might prove a “rope of sand,” and the way to an honorable compromise would open.

James Buchanan

Hand-colored Engraving by John Chester Buttre, 1857,

After Painting by Alonzo Chappel

The retiring President remained in Washington to witness the inauguration of his successor in office, Abraham Lincoln, shortly afterwards going to his home in Wheatland, Pennsylvania, where he passed the uneventful years until the time of his death, June 1, 1868. During this period he prepared and published a defense of his administration, an interesting work, throwing much light upon

James Buchanan

by John Henry Brown, c. 1865

the question at issue and the motives by which his actions were guided. This defense confirmed the estimate now so generally placed upon his character, that he was not unpatriotic in feeling or purpose, and that he was opposed to the principles of secession. The judgment hastily given concerning President Buchanan during his lifetime, seems more harsh than is warranted by the facts presented in the clearer light of dispassionate, historical record to-day. His mistakes and errors were many, but his surroundings called for exceptional qualities rarely combined in the individual life, and few men, situated as he was, would have been equal to the demand.

Among the many offices of public trust that Mr. Buchanan filled, he served perhaps the most acceptably in his diplomatic relations with foreign countries. He was distinguished in his bearing, had much grace and tact in his intercourse with the representative men from different nations, and was more firm in negotiation when representing his country’s interests abroad than in his policy to preserve the American Union.

James Buchanan

by Augustus J. Beck

Although criticised so widely, his moral character was never assailed, amid all the bitterness of denunciation which attacked his public career. He was never married, but he had an underlying vein of tenderness in his nature, possessed a kindly, genial disposition, was most interesting in conversation, a pleasant acquaintance, a true friend. Called to the Presidency at a most trying time in the Nation’s history, he ought not to be judged apart from the environments of his position, which should serve as excuses for some of his errors, while throwing into greater prominence the virtues of his unsullied character, his acknowledged integrity, his abilities and activities.