"Too Late to Dodge, Too Close to Run" article by Thomas J. Fleming.

Published in Special Story Edition, The Virginian-Pilot, September 6, 1964

|

"You win or lose, live or die - the difference is an eyelash." - Douglas MacArthur

"Too Late to Dodge, Too Close to Run" article

by Thomas J. Fleming.

Published in Special Story Edition, The Virginian-Pilot, September 6,

1964

In the twilight of March 11, 1942, Douglas MacArthur walked slowly out on a tiny dock beside a scarred and scorched rock called Corregidor, and paused to look back at the big guns, still belching defiance from the batteries topside. In the distance other heavy guns boomed on a battered peninsula called Bataan, where 70,000 exhausted, starving Filipino and American soldiers fought with desperate faith that either reinforcements or MacArthur's genius would somehow rescue them from capture and death.

But MacArthur, the general who had rallied and led them in their brilliant defense, which had already disrupted the Japanese timetable for the conquest of the South Pacific, was being forced to make the most daring - and heartbreaking - decision of his career. By direct order of the President of the United States, he was about to attempt an epic escape from the enemy surrounding him.

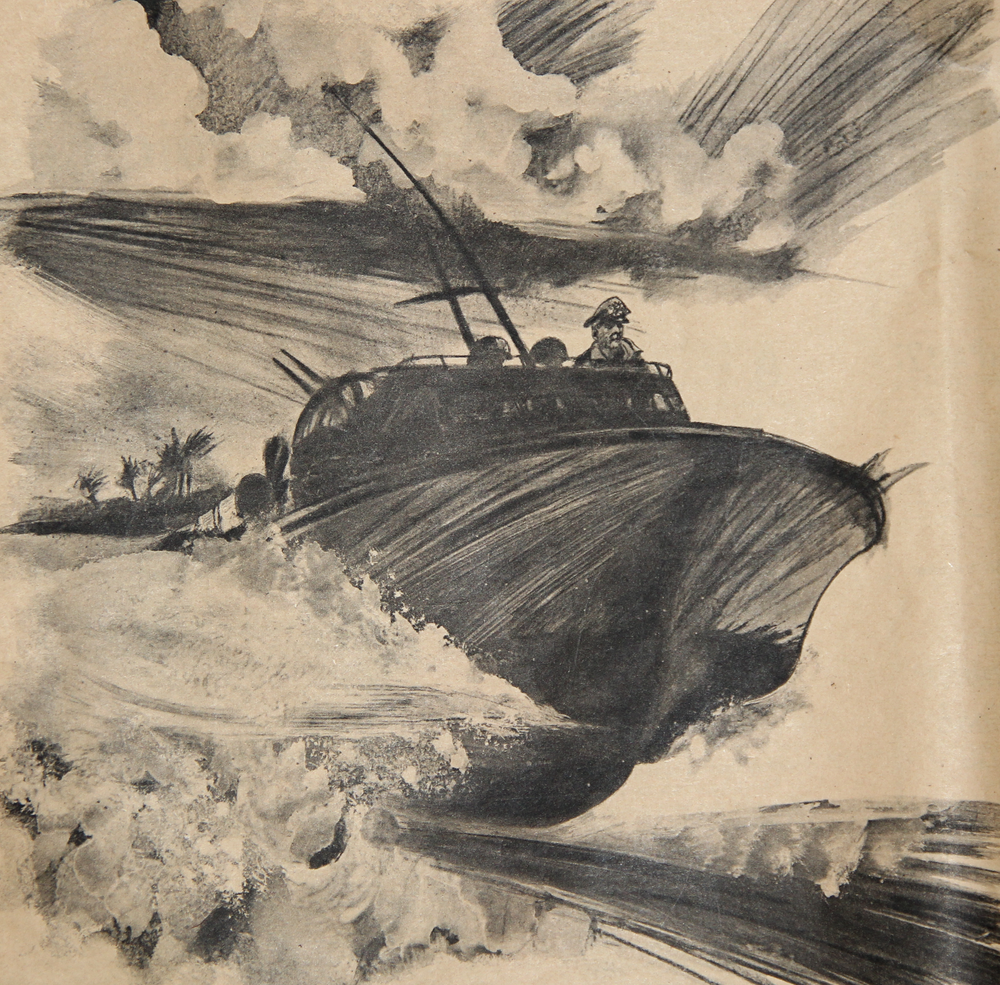

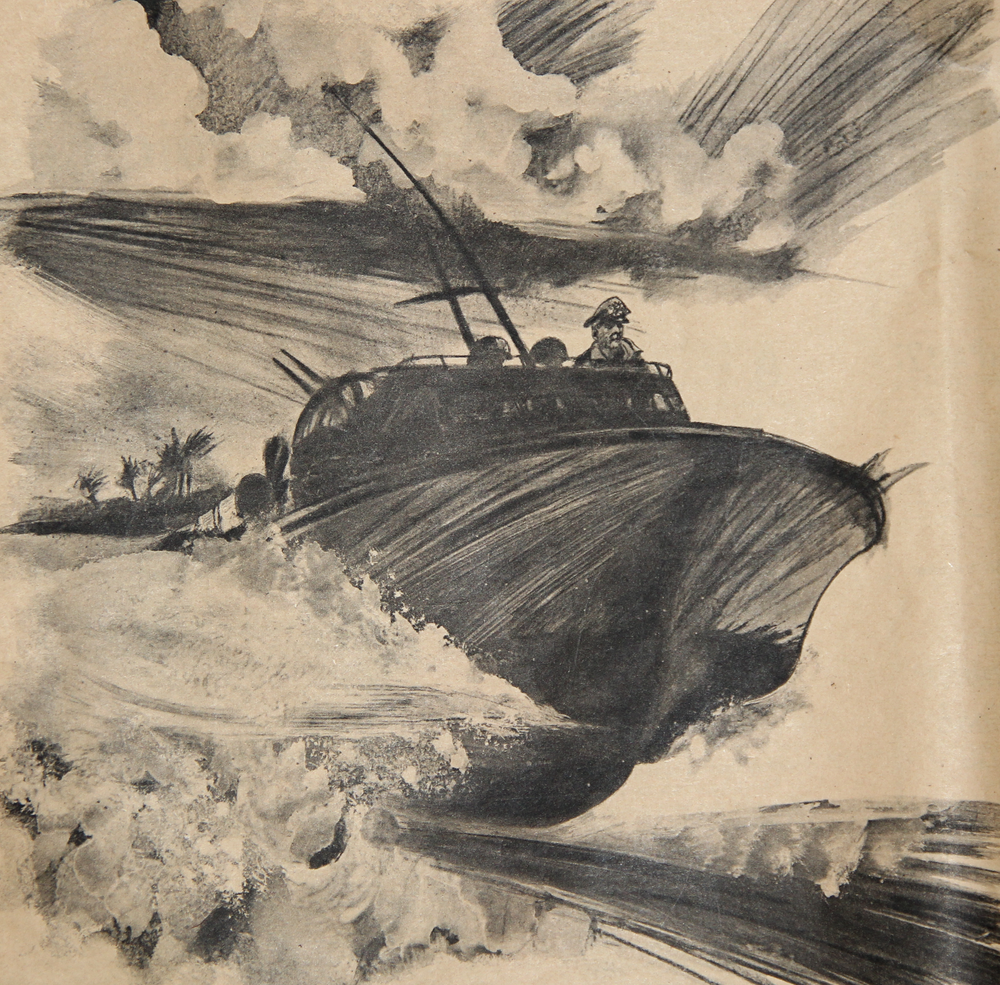

At the dock, their 4,000 horsepower Packard motors rumbling in their 70-foot hulls, were four PT boats . . .

Out into the dark harbor moved the little flotilla. With excruciating care, they picked their way through the minefields, and then, with throttles wide open, began their race for their first refuge, the uninhabited Cuyo Islands. The weather grew foul, and mounting waves flung the small boats around until MacArthur said he felt "as though I were in a cocktail shaker." His wife cared for his four-year-old son, and their Chinese nurse, Ah Cheu, who were wretchedly seasick, as were most of the General's 18-man staff. Along the shore, huge bonfires came aglow, as the Japanese signaled to their ships at sea that the PT's were on the prowl. Soon against the night horizon loomed the sinister black blotches of the blockading fleet.

Motors were cut, and the little boats lay in a trough of tossing sea, waiting for the challenge of a crashing gun. MacArthur and Bulkeley [commander of the PT boats] had already worked out a plan - not to run, but to attack with all their torpedoes, then scatter. But not so much as a questioning blinker came from the Japanese cruisers and destroyers. The PT's lay too low in the heavy seas for their lookouts peering through the night. "Put her hard to starboard," Bulkeley snapped, and they ran for the Cuyos.

The weather worsened, and the boats became separated. Number 2 boat was the first to reach their rendezvous. In the morning mist, it mistook MacArthur's Number 1 boat for a Japanese destroyer, jettisoned its fuel, and came within a split second of opening fire. Only a glimpse of MacArthur's figure standing in the bow averted imminent tragedy.

They wasted most of the day under camouflage waiting for Number 4 boat, while Japanese search planes droned overhead. Giving up, and jamming the personnel of fuel-shy Number 2 aboard the other two boats, they ran for the island of Mindanao. The night was clear, but high wind threw up mountainous seas. Suddenly, through the blackness loomed a huge shape: a Jap battleship. "It was too late to dodge, too close to run," said one of MacArthur's staff later. "The only hope was to cut the engines, lie still and make the sign of the cross."

Mistaking them for fishing boats, the battlewagon steamed solemnly past without a challenge. By morning they were ashore at Del Monte airfield in Mindanao, where planes were to ferry them to Australia. But there were no planes. All day and all night they waited, while Japanese ground forces came closer and closer to Del Monte. In a fantastic snafu, the Navy Commander in Australia had refused to lend new flying fortresses under his command to the Army for the mission. The Army had sent four patched together B-17's; two crashed, one turned back, and the other landed without brakes or superchargers and MacArthur refused to board it. Finally the Navy relented, and released three planes. Two arrived, and MacArthur decided the risk of overloading was less than the steadily advancing Japanese. On the third night of their vigil, with the MacArthur party crouched in gun blisters and lying in the fuselage to give the lumbering bombers balance, they took off. Going down the runway an engine on the first plane sputtered, missed, sputtered and took hold only at the last possible moment.

Zeros filled the sky above Japanese-held Timor, but they missed their prey in the darkness. The next morning MacArthur landed at Darwin and within an hour the pursuing Japs pulverized the field with bombs. Again their intended victim was a step ahead of them.

Never before had a Commanding General and his staff escaped through 2,500 miles of enemy-held territory. While the war lasted, MacArthur never referred to his exploit as an escape. He insisted it was like a dash from a beleagured garrison in the old West "to bring up the Cavalry." His promise to the Philippines, "I shall return," was in this tradition. Privately, he had no illusion. "It was close," he told one of his staff, "but that's the way it is in war. You win or lose, live or die - and the difference is just an eyelash."

(Ray Winstead: For my father's opinion of General MacArthur see my note under Part 3 of http://raywinstead.com/edw/edwautobio.shtm )

Back to Dr. Ray Winstead's Front Page