Click an Image for Full Size

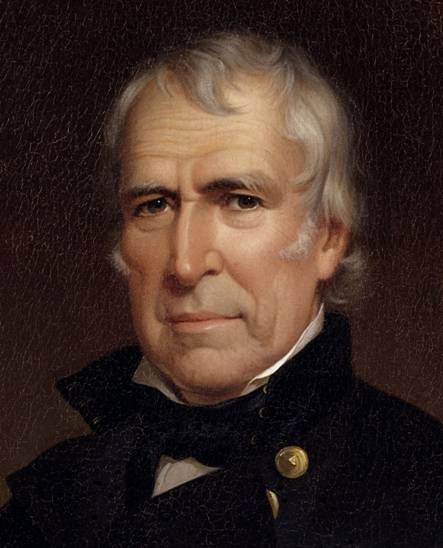

ZACHARY TAYLOR

Twelfth President,

March 4, 1849 – July 9,

1850

![]()

Franklin P. Rice, 1882:

ZACHARY TAYLOR, the Twelfth President of the United States, was born in Orange County, Virginia, September 24th, 1784. He received little education, and remained upon his father’s plantation until his twenty-fourth year. He was Commissioned as first lieutenant in 1808; and was made captain in 1810. For his service in the War of 1812, he received the rank of major; and he continued with the army until his election as President, taking part in several Indian wars and in the Mexican war. He was made a Major General in 1846. For his successes in Mexico he received the thanks of Congress and a gold medal; and was presented by the Whig Convention of 1848 as an available candidate, and triumphantly elected. He became President March 4th, 1849, and died in office July 9th, 1850.

Zachary Taylor was elevated to the Presidency by popularity acquired in a war which had been unpopular with his party. His personal fitness for civil administration was questioned even by his supporters, for he knew nothing of political matters, had never cast a vote in his life, and probably could have given no satisfactory reason for being a Whig rather than a Democrat. The duties of his office were, however, discharged in a creditable manner, and his popularity increased, especially in the Free States. His term is memorable as the period when the antagonism between the free and slave sections reached a crisis, which was averted by measures he did not live to see consummated. Simplicity and straightforwardness were his prominent characteristics, and he evidently intended to do his duty to the whole country. His character as a military man is indicated by the term, “Rough and Ready,” applied to him by his soldiers.

![]()

Henry W. Rugg, 1888:

IN LOOKING backward to the men foremost in establishing this Republic, they compare favorably with those prominent in the American history of to-day. It is only when we regard the outward conditions of this new world, then and now, that we come to realize the great progress of the Nation in all that makes for the best civilization. Men were heroes and leaders in those early days; but the material resources, now available for the service of American interests, were not theirs to command, while the story of early struggles in the wilderness indicates the great strides which comparatively few years have witnessed in the material prosperity of our country. With a foundation into which has gone the sacrifice and work of men honored in every time, the future results could not fail to be those of successful achievement; but the rapid growth in all the advantages of civilization has far exceeded the limits prophesied of by the fathers. Up to the life time of the twelfth President of this Republic the West and South were lacking in many extrinsic aids to prosperity. Although Zachary Taylor was born November 24, 1784, in Orange County, Virginia, his parents, the year following, removed to Louisville, Kentucky, and the lad was brought up in this little settlement, the humble beginning of the prosperous city which now bears the name.

This rough life, combined with the inherited tendencies from his father, a trusty soldier of the Revolution, brought out the military qualities and likings which were so soon apparent in the boyish nature. He was a soldier from the very beginning, not as all boys are who play with toy-drums and wear a miniature sword, but as one who fully realized what duty to his country meant, the hardships it involved. In the training as a farmer’s boy, as well as during the little school education which he received, he was decisive and quick in his actions, somewhat blunt, yet frank in speech, honest in thought and deed, impetuous, ready to encounter personal risk, yet obedient, as he felt every true soldier ought to be.

Zachary Taylor

by George P. A. Healy, 1860

Colonel Taylor was as much delighted as his son Zachary, when, in 1808, the young man, then twenty-four years of age, received a commission as Lieutenant in the United States army. There was no question in his mind as to whether or not he should accept the position; he felt that he was fitted for a soldier, and applying himself diligently to the duties required, he soon came to be regarded as a capable, trustworthy officer. It was about this time that he married Miss Margaret Smith, whose home was in Maryland.

The Indian attack led by the famous chief Tecumseh against Fort Harrison was an opportunity for Captain Taylor, who, in defense of the fort, gained distinction for his courage and skill. He was publicly complimented by General Hopkins for his conduct of

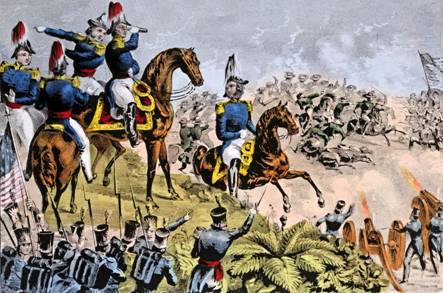

General Taylor

at the Battle of Buena Vista

Chromolithograph by Sarony & Major, c. 1847

this affair and was promoted to the rank of Major. His energy and coolness characterized his leadership in the various movements against the British and Indians, which were terminated by the restoration of peace with Great Britain, in 1815. At that time Major Taylor resigned his commission, his intention being to engage in agricultural pursuits for a time at his home in Louisville. After a year spent in this way he was re-instated in the army, resuming his duties with renewed ardor, rendering such efficient service that he was promoted to the rank of Colonel in 1832. He was extremely popular among the soldiers because he cheerfully bore his part with them in any danger or hardship, and had a stock of sound common sense which they could respect. His early opportunities had been few, but he had profited by his experiences; was skilled in Indian warfare; his habits of discipline and study still aided him, and he became an intrepid, wise commander.

The conduct of the Seminole war aroused much criticism in the United States because of an alleged undue harshness in dealing with that ferocious tribe of Indians. Its result, in the dispersion of the Seminoles to the west banks of the Mississippi caused general

“A Little More

Grape Capt. Bragg”

“General Taylor at the Battle of Buena Vista Feby 23d, 1847”

Chromolithograph by N. Currier

of Cameron painting, c. 1847

satisfaction, however, and was a signal victory for Colonel Taylor, who, by reason of his military skill and services in this connection, was elevated to the rank of Brigadier-General and appointed to the chief command of the army of the Southwest. During this time, while faithfully, yet in a very quiet manner, discharging his military duties, he bought a plantation near Baton Rouge, La., where he established his family in a comfortable, well cared for home.

It was not possible, however, for a military man like General Taylor to remain in obscurity while his country was agitated by the difficulties brought into prominence during the presidential campaign of 1844. Mr. Polk, a friend of slavery, and a pronounced champion of the annexation of Texas, was the successful candidate for election as President, and in this state of affairs it became apparent that war with Mexico was inevitable. General Taylor was directed to hold his troops in readiness for service along the frontier. He did this, but refused to enter upon aggressive measures to bring about a collision with Mexico, or to undertake any forward movements upon his own responsibility. As a good soldier he waited for instructions and obeyed orders. In March, 1846, in accordance with a command from President Polk, General Taylor advanced his army to the banks of the Rio Grande, claimed as the boundary line between Texas and Mexico. The Mexican government had already ordered its troops to the same locality, so that it was evident a conflict must soon take place.

During the months of April and May, 1846, the American army met the enemy in several severe engagements, being victors in every case. In his official reports concerning these General Taylor said: “Our victory has been decisive. A small force has overcome immense odds of the best troops that Mexico can furnish – veteran regiments perfectly equipped and appointed. Eight pieces of artillery, several colors and standards, a great number of prisoners, including fourteen officers, and a large amount of baggage and personal property have fallen into our hands. The causes of victory are doubtless to be found in the superior quality of our officers and men.”

The conduct of the commanding officer in all these engagements was worthy of the praise it called forth from military men and those in authority. Congress conferred the rank of Major-General upon the successful commander, and complimented his bravery by appropriate resolutions. So much of confidence was felt in his abilities as a military leader that his troops were reinforced by volunteers, money and supplies were voted him, and he was thus prepared for the encounters which quickly followed.

The battle of Monterey was won by the Americans after days of hard fighting, against great odds, both of position and numbers, General Ampudia leading the defeated forces. General Taylor’s course in treating with the Mexicans was criticised on the ground that he had allowed them too favorable terms. This occasion of dissatisfaction with him, felt at Washington, together with the influence of political intrigues, perhaps, caused the order, given to a considerable part of General Taylor’s troops, that they should join the force of General Scott, then about to attack Vera Cruz, preparatory to his contemplated advance on the City of Mexico. General Taylor showed his patriotism, his true soldierly instincts, by obeying this order to send the best part of his troops to the

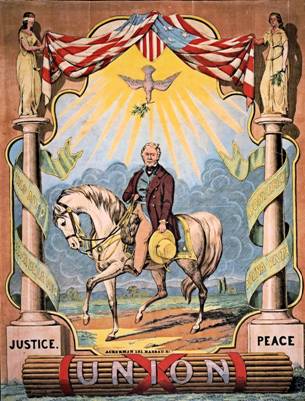

“General

Taylor and Staff: The Heroes of Palo Alto,

Reseca de la Palma, Monterey, and Buena Vista”

Chromolithograph by N. Currier, c. 1847

support of General Scott, changing his plans so as to stand, for the time, only on the defensive.

General Santa Anna saw what seemed to be his opportunity to crush the reduced forces under General Taylor, and moved rapidly upon them with his large, well-disciplined army, giving battle at the pass of Buena Vista, February 22, 1847. Although this encounter did not end the war, it being left with General Scott to conduct skillful military operations until the capital of Mexico was taken and the spirit of its people broken, it was in fact the turning point of the long struggle, and properly ranks as one of the most notable battles in American history. During the two days’ fighting at Buena Vista, General Taylor displayed again his qualities of military leadership, showing judgment in selecting the position for his men and in directing their movements, while he inspired his troops to bravery by his own courage and his coolness in confronting the dangers to which he was constantly exposed.

The country, thoroughly awakened to the heroic virtue of General Taylor, now rang with his praises; “Old Rough and Ready” was transformed into the “hero of Buena Vista.” His growing fame and popularity caused him to be spoken of as a candidate for the presidency. General Taylor distrusted his fitness for that position. He had taken no part in political affairs, had seldom voted, and had never held public office. He was, however, nominated by the Whig Convention held in Philadelphia, June 1, 1848, and elected President in the November following, over General Lewis Cass, the Democratic candidate, and ex-President Van Buren, candidate of the Free Soil party.

President Taylor was inaugurated at Washington, March 4, 1849, after having resigned his army commission with a record for forty years’ consecutive military service. He was greatly tried and perplexed during his administration of political affairs. His training had not been that of a statesman or political leader, but his natural shrewdness, his practical judgment, his insight into what was best for his country, enabled him to do excellent service as the executive head of the government. The exciting questions of slavery were still agitated through the land, the purchase of Cuba and the admission of California caused much feeling and discussion. The President helped still the waves of dissension, won the hearts of those associated with him in administering the government, while his

Zachary Taylor

Campaign Poster

Woodcut Print on wove paper in five colors

by Thomas W. Strong and James Ackerman, c. 1848

countrymen generally appreciated his efforts to faithfully discharge the duties of his position, never shirking the responsibilities which at times weighed heavily upon him.

It was after a year of conflict, more trying to the great soldier than all his encounters on the battle field, that President Taylor ended his mortal career, dying, after a brief illness, July 9, 1850, one year, four months, and five days after his inauguration. Everywhere in the land there was mourning for the kindly man, the gallant soldier, who had so warm a place in the affections of the American people.

The story of the Mexican war, possessed of much romantic historical interest, is inseparably connected with the fame of General Taylor, making evident his prowess in the conduct of battles, and his reputation as a popular officer to whom his troops were personally attached. More frequently is he remembered as the hero of Buena Vista than as America’s Chief Magistrate, though in the latter position he was far from being a nonentity or unfitted for his responsible duties. A true man is of value to his country whatever his capacities, if an honest heart beats in defense of his nation’s liberty, of truth and the right. President Taylor was this and more. He was plain, simple in his tastes, possessed of little scholastic learning, yet his intellectual powers were not to be denied, his sound, practical wisdom not to be gainsaid. His life was not spent in the political arena, yet he had learned enough of statesmanship to skillfully grapple with the issues of the day, to shrewdly estimate men and affairs, so that he was not often misled or easily influenced. His pleasant, cordial manners did not proceed from a weak desire to court favor, but expressed his sympathetic feelings, which, however, did not lead him into errors of judgment or to vacillating opinions. As a quick, bold, decisive commander of armies, so he was an energetic, firm President, his true patriotism urging him to every service which his country might command. Carried into office by the enthusiasm which his great generalship had aroused, he did not allow himself to be regarded simply as the popular hero of the hour; he at once directed his energies to establishing his reputation as President upon something more enduring than the reflected glory of his military career; he was sincere, faithful to every trust committed to his keeping, a man of the people, a representative American, worthy to be enrolled among the noble few whose names are interwoven with the fibre of our national existence.

![]()

Zachary Taylor

by Joseph Henry Bush, 1848