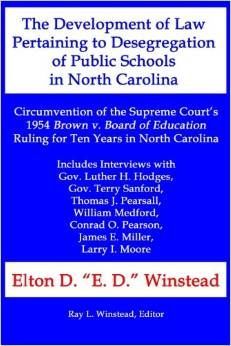

Celebrating

E. D. Winstead's Life

E. D. Winstead's 1966 Doctoral Dissertation:

This book

is the dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the

degree of Doctor of Education in the Department of Education in the Graduate

School of Arts and Sciences of Duke University, Durham, North Carolina in 1966

by my father Elton D. Winstead. The information in this book has historical

significance and deserves to be more readily available as a contemporary

perspective during that time period leading up to the desegregation of the North

Carolina school system. A reflection on this perspective is especially

appropriate now on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the 1954

Supreme Court ruling in the Brown v. Board of Education

case and on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the passage of

the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The 1964 Civil Rights Act basically ended North

Carolina’s Pearsall Plan, not only as a way to preserve the North Carolina

school system, but also as a way to circumvent the Supreme Court ruling in the

Brown v. Board of Education case.

The Pearsall Plan, as the vehicle for the circumvention of

the Brown decision, was declared to be unconstitutional by federal courts

in two class-action cases in 1966 and 1969 after this study was completed, and

two of the people interviewed in this study were instrumental in those cases.

In Hawkins v. North Carolina Board of

Education the U. S. Department of Justice intervened under the 1964 Civil

Rights Act, and Mr. William Medford, ironically, as U. S. District Attorney

supported the plaintiffs.

He told the court (according to a newspaper article)

that he was personally on the committee led by Thomas Pearsall that formulated

the plan, that as a state senator he had also helped to guide it through the

General Assembly, and even though he thought the law had been useful at the time

to ease the shock of immediate desegregation, he also concluded that “This

statute and what it was ultimately trying to do is unconstitutional.” The

Pearsall plan was declared to be unconstitutional by the court on March 31,

1966. In the 1969 class-action case

Godwin v. Johnston County Board of Education

Mr. Conrad O. Pearson, General Counsel for NAACP for North Carolina, also

interviewed in this study, was the lead attorney for the plaintiffs.

The Pearsall plan was declared to be

unconstitutional by that court on July 8, 1969.

As editor of this 2014 edition I retyped the dissertation

to provide a version easier to read than simply scanning a copy of the original

typed by my father on a mechanical typewriter at home. (The original, mostly

double-spaced, typed dissertation is 279 pages long.) A new subtitle was added

indicating a main conclusion of the study. A few format changes have also been

added to the new edition, e.g. the summary list above of people interviewed was

not included in the original dissertation, and the formats of the tables in the

appendix have been modified. As in the original dissertation the interviews are

included in the appendix.

A few selected conclusions from the

study:

“Based on the official position taken in North Carolina toward the Supreme Court

decision of May 17, 1954, and a review of pertinent court cases, the following

conclusions as to the law pertaining to desegregation of the public schools in

North Carolina may be drawn.”

“1.

The approach to the problem was to circumvent the

decision by legislation.”

“2.

The vehicle designed to circumvent the decision was the

Pupil Assignment Act and the Constitutional

Amendment.”

“3.

The enactment of the Pupil Assignment Act and the

Constitutional Amendment in North Carolina was a

deliberate attempt to provide the individual a means of

avoiding compliance with the Court’s decision and has

tended to perpetuate the bi-racial school system in North

Carolina.”

Furthermore:

“The Civil Rights Act of 1964 interjects an economic element into the

desegregation problem. The threat of the loss of large sums of Federal aid

which are available to school districts has caused the desegregation of more

schools than the previous decade of litigation in North Carolina had effected.”

“If, as stated in the School Segregation Cases, the Supreme

Court held that segregation and discrimination were synonymous, and that

separate educational facilities are inherently unequal and a violation of the

guarantees of the Fourteenth Amendment, then there is general discrimination on

account of race in the public schools of North Carolina. As the term is defined

in this study, there are no integrated school districts in North Carolina and no

conclusive evidence which indicates that the North Carolina Public School System

is not, in fact, a bi-racial system.”

“Some of the persons closest to, and most influential in

shaping, North Carolina’s official reaction to the 1954 Supreme Court decision

in the Brown case were interviewed, and their comments made a decade

after the decision are reported.”

A few selected quotes from the

interviews:

Question: The Report of the Supreme Court Decision

of May 17, 1954 by the Institute of Government at Chapel Hill discussed the

alternatives open to the State, and the alternatives appear to boil down to

three possibilities; that is, as stated in the report, defiance,

compliance, or to play for time, making haste slowly enough to avoid

litigation, and yet make haste fast enough to come within the law; thereby

keeping the peace and keeping the schools.

I

have simplified the third alternative by calling it what it appears to be –

circumvention, which of course, means to go around, to gain advantage over

by artfulness or stratagem.

Do you agree that the three possibilities cover the alternatives available to

North Carolina at the time?

Mr. Conrad O.

Pearson: “Yes, and North Carolina followed the alternative offered by

circumvention.”

Mr. Conrad O.

Pearson:

“The committee [The Special Advisory Committee appointed by

the Governor] took a negative approach. They made no effort to influence public

opinion toward compliance with the Court’s decision.”

Gov. Luther H. Hodges:

“I did not practice circumvention. We did make an effort to play for time.”

“At all times, the paramount consideration was that we must

obey the law. We were sincerely trying to see if certain changes could be

affected by new legislation.”

“We tried to keep the schools open. For example, at a

meeting in Wilmington last night, I was introduced as the one who was

responsible for ‘not a child lost a day of school’ in North Carolina as a result

of the Brown decision.”

Gov. Terry Sanford:

“I would say that the vast majority of the people in North Carolina did not like

the Brown decision, and even those that felt that it had to come, looked

at it with a certain amount of regret.”

“And even those that felt that segregation in the schools

should end looked with considerable dismay at it because of the possible

violence and the difficulties that they knew would follow.”

“As I understand what Governor Hodges said at the time,

there was a determination that North Carolina would not defy the court, and

there was a feeling that the instantaneous compliance was not feasible. Not

even desirable. I personally don’t feel that Governor Hodges and the Pearsall

Committee were trying to get around the decision as much as they were attempting

to soften the effects of it.”

Question: Did the committee

[Special Advisory Committee, chaired by you] ever seriously

consider immediate desegregation as a

possible solution?

Dr. Thomas J. Pearsall: “No.”

Mr. Larry I. Moore:

“The Pearsall Plan made possible a more orderly

transition.”

“At that time, if North Carolina had integrated the schools

in proportion to population ratios, the school system would have been destroyed

and there would have been riots. The people would not have accepted

integration.”

Dr. Thomas J.

Pearsall:

“For all practical purposes the 1964 Civil Rights Act

voided the effects of the Pearsall Plan. We no longer have to deal with a Court

decision but are dealing with social legislation from the Congress.”

The modern reader will notice that word choice has changed

since 1966, when the word “Negro” was standard terminology, for example, as used

by Mr. Conrad O. Pearson, the General Counsel for the North Carolina NAACP in

his interview published in the appendix of this book.

My father gave me permission to publish his dissertation.

Ray L. Winstead

Editor

Back to EDW Front Page

Back to Dr. Ray Winstead's Front Page